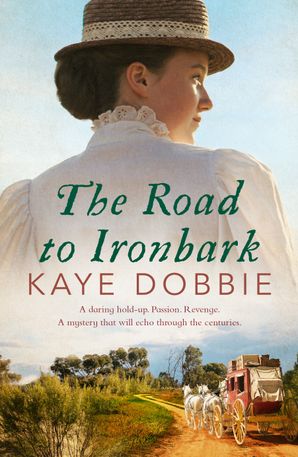

A daring hold-up. Passion. Revenge. A mystery that will echo through the centuries. A compelling romantic adventure, perfect for readers who love Darry Fraser.

1874,The Victorian Goldfields

In the town of Ironbark, Aurora Scott faces ruin as the railways supplant the Cobb & Co coach line, the lifeline of her hotel. Aurora is no stranger to adversity; the formidable publican has pulled herself from a murky past to build a respectable life in Ironbark. But when bushrangers storm the hotel, taking hostages as leverage for the Starburst Mine’s payroll, Aurora has more trouble on her hands than she can handle.

This is no random act, but a complex scheme of revenge. The gang turn on each other. Shots ring out. And when the dust settles, the money has vanished, and so has Aurora Scott…

After 150 years, the mystery of the missing payroll has passed into folklore. And when journalist Melody Lawson helps her brother prepare for the town’s annual Gold Hunt Weekend, she is just as drawn into the past as the tourists. But with a surprise inheritance her own family history becomes a puzzle, bound up with the fabled payroll – and as Melody follows the clues, danger mounts…

PRAISE FOR KAYE DOBBIE:

‘Kaye Dobbie has written a spellbinding tale of intrigue and mystery in … which she deftly weaves two very different time periods into one unforgettable story.’ – Beauty and Lace

‘A rich and vibrant picture of rural Australia and a bygone time.’ – The Daily Telegraph

AURORA

1855, Leon Armstrong’s Goldfield Entertainers, Ballarat, Victoria

Aurora Patterson had been painting for hours, using the dull light that shone in from the high windows in this backstage area. The wooden panels, propped up against the wall, were background for tonight’s performance. Mr Armstrong had wanted a change from the dark and badly chipped forest scene they had been using until now.

‘Something cheery,’ he’d said, looking as dapper as usual in his brown coat and beige breeches. ‘Evidently you can paint, Aurora.’ It wasn’t a question, but his eyes were doubtful.

‘I can,’ she’d assured him, wondering if he thought her too young. She didn’t think it was because she was a female—there were plenty of women employed by his theatre company, The Goldfield Entertainers. ‘I’m seventeen,’ she’d added.

He’d smiled and she’d felt her heart flutter like a butterfly. Leon Armstrong was a handsome man in the prime of life and she’d seen plenty of women turn for a second look at him.

‘If Cecil thinks you can do the job, then that’s good enough for me,’ he’d said.

Cecil was employed to repair the stage props and organise any extra items needed by the various acts in Mr Armstrong’s company. When Aurora answered the advertisement pinned to the theatre door, Artist wanted, he had asked her to paint him a bowl of fruit. She was only halfway done when he’d hired her.

The background for tonight’s performance was a big job, and Aurora wondered now if her masterpiece was cheery enough. She had decided on a lakeside scene and a castle, with a flag flying from the tower. Most of the miners paying to watch the Goldfield Entertainers were from somewhere other than Ballarat, and they must be weary of the bare, sparsely treed landscape that the goldfields had become.

She stood up, shaking out her crumpled skirts and smoothing the sleeves of the well-worn woollen jacket down her arms. Lately, not only did it provide comfort, it also served to keep out the cold. It was a man’s jacket, one her father had left behind the last time he was home.

Her mother was buried in a graveyard outside the town of Leighton, fifty miles south of here. For three years she and her younger sister Ellen, had lived in Leighton, while her father came and went, seeking work.

He was a portrait painter, and travelled from town to town, looking for clients. When he’d begun to train Aurora, he had only allowed her to paint the backgrounds. It wasn’t until she was proficient at that could she move on to a pot here, a vase there, some rose petals lying curled across a glossy table. Eventually, he’d trusted her enough to do some of the important work, and when he’d been tasked with painting a portrait of Leighton’s mayor, it was Aurora’s brushstrokes that had captured the gentleman’s bristly moustache and arching eyebrows.

She had known she could do more, but her father wasn’t in a hurry. ‘You have talent,’ he’d told her. ‘Soon we’ll be able to travel together and earn twice as much.’

That was the last thing he’d said to her as he’d set off that final morning. When he hadn’t come back after six months, Aurora knew he must be sick or injured, because she didn’t believe he would abandon his two daughters. It was a sobering thought, particularly as Aurora was now the head of her family and tasked with looking after Ellen.

She stretched her aching back. Somewhere in the backstage area, she could hear one of the older actors practising his lines—Ellen said he was always forgetting them—but the audiences liked him, so Mr Armstrong kept him on. Or perhaps that was because the actor was willing to take less pay than previously. Rumour was, the company was struggling to make a profit.

Aurora was just glad to have work. It was a relief when Ellen had also been taken on by Mr Armstrong. She was kept busy sweeping floors and helping to mend costumes, and any other menial task no one else could be bothered doing.

‘Haven’t you finished yet?’

Before she turned her head, Aurora dabbed a few apples on one of the trees in an orchard beside the castle. Thirteen year old Ellen was standing behind her, fair hair untidy and her blue eyes too big for her heart-shaped face. She began to chew her nails, a nervous habit, and the strawberry blotch on her left shoulder—the birthmark that looked like a scald—peeped out from under her neckline and caught Aurora’s eye. Apart from that blemish, Ellen was delicate and pretty, and took after their mother. When she smiled she had even been called beautiful.

‘It has to be right,’ Aurora said now, stepping back to examine the tree. Perhaps the lake needed some swans.

‘No one is going to notice if it isn’t perfect,’ Ellen retorted.

‘I will notice it.’

Ellen huffed, stepping from foot to foot. ‘You said you’d take me to the library,’ she whined. ‘Tonight’s show starts in an hour. We won’t have time if we don’t go now.’

Aurora hesitated, but the painting wasn’t right, and she had learned from her father how important it was to make something right. She leaned back in with her brush, quickly adding a swan, and then another smaller one.

‘I won’t get paid if it isn’t good enough,’ she said.

‘It’s already perfect. Please, Aurora! I want to borrow a book.’

Ellen had rarely attended school, and now she was working there was no time. Still, she was intelligent and already able to read better than Aurora, so her sister did not worry about it too much. There were more important things than the classroom.

At least Ellen could still be a child. Aurora had had to grow up quickly since having to take charge. There were times, like now, when she remembered with some resentment that she too had once been a child, and her father’s favourite.

She recalled sitting with him in the evenings, when Ellen was in bed. One conversation they had had was still clear in her mind. He’d been smiling, and then gently tugged the end of her braid—her dark hair was wild and needed to be constrained if she was to get a comb through it. ‘This isn’t forever,’ he’d said. ‘One day, someone rich and famous will hear of me. I’ll paint their portrait and then we’ll be set.’

Aurora had taken on his dream as her own. One day, she told herself. One day.

Voices from inside one of the nearby rooms caught her attention. The door was open and she saw Mr Armstrong standing there, tall and handsome, his golden hair brushed back from his brow. Aurora sighed inwardly, feeding her secret passion for her employer, even if she knew he would never see her in that way. She barely glanced at the man who was standing beside him, other than to notice his hair was dark and he wore a fine frock coat and shiny boots.

As if her regard had caught his attention, the stranger turned his head to stare at her, and then his gaze slid past her, to Ellen.

Aurora also looked at her sister and was glad Ellen hadn’t noticed him. There was something unsavoury in the man’s expression. The goldfields weren’t safe, and Aurora knew they were lucky to have been taken in by the company. When they had set out to look for their father, they had headed to Ballarat, thinking that was the most likely place, but they never found him. Instead, they found Leon Armstrong, and his ragtag band of players and dancers and musicians. This was now their home.

Aurora added a few more brushstrokes to the painting and when she looked up again the two men were gone.

‘Aurora,’ Ellen groaned.

‘All right,’ she said, and carefully wiped her brush. ‘We must be quick. One of the chorus girls is ill, and I’m to dance in her place tonight.’

Ellen giggled at the thought, nudging her sister as they hurried out into the street and down the hill towards the library. ‘You’ll likely fall over your own feet,’ she teased.

‘I’ll be in the back row, so if I do no one will see me.’

By the time Ellen had chosen her book—Dickens’s David Copperfield—they had to run. As they slipped inside the large building that housed the theatre, the first act was already on. Aurora tugged Ellen’s hand, leading her through to the area where the dressing rooms were situated. She would need to hurry to get into her costume.

‘Ooh, are you going to be wearing one of those short skirts?’ Ellen goaded.

As she turned to reply to her sister, Aurora caught a glimpse of a man standing in the shadows. Watching them. She thought it might be the same man who had been with Mr Armstrong, but the thought was fleeting, and then she forgot him.

That night, it turned out Aurora’s dancing was far better than anyone had imagined. She surprised herself. The beat of the music, the blur of the crowd, the sensual movements of her body swaying and turning … The girl she was disappeared and became someone else entirely. Ellen’s teasing had worried her a little. Aurora had thought she would look foolish, and now she couldn’t wait to tell her sister she had been wrong. There had been a moment when she was spinning in the dance when she had thought she saw her sister’s face. Eyes wide, mouth agape. As if she was cheering Aurora on, or calling out to her. It was only an instant, and when Aurora turned again she was gone. When she finished, she was in a hurry to get to Ellen.

‘Aurora!’

The voice brought her around. It was Mr Armstrong. He was full of praise, his blue eyes sliding over her as if he had never seen her before. ‘Aurora, when you are on the stage you glow. It is impossible to look away.’

She searched his face, trying to decide if he was telling her the truth. ‘Do I?’

‘Believe me, you are something special. Tomorrow night you can start in the front row,’ he went on. ‘I want everyone to see you.’

Her earlier concerns forgotten, Aurora was bubbling with excitement as she hurried off to find Ellen. Her sister usually hung around where the food vendors set up their stalls.

She wasn’t there.

Aurora looked, her anxiety returning, but Ellen couldn’t be found. After she had searched everywhere she could think of, Cecil helped her search again. They couldn’t find her. Others joined in the search, yet it was as if the girl had vanished into thin air.

I’ve lost my father and now my sister. How can that be? I don’t want to be all alone.

When morning came, Aurora stood in the doorway of the theatre, her father’s jacket wrapped tightly around her, and looked out over the town and the vast goldfields where so many fortunes had been won and lost. She kept telling herself that this couldn’t be happening, that it was a mistake. Or was it a dream? She closed her eyes, praying that when she opened them again, her sister would be standing before her, apologising for whatever she’d been doing all this time.

When she opened her eyes, though, Ellen was still missing. A bleakness began to settle over her.

‘We’ll find her,’ Mr Armstrong had promised her when he’d been told the news.

Aurora wiped the tears from her face, telling herself it would be all right. Ellen would come back and everything would be all right. How could it be otherwise?

And yet there was a hollow feeling in her chest that felt like grief. Ellen would never wander off alone without telling her sister, and besides, she had a new book to read. She should be curled up in her bed and lost in the story.

This was all wrong, so very wrong.

Aurora had a dreadful feeling that she was never going to see her sister again.

MELODY

24 September 2017, Melbourne, Victoria

I had spent the morning putting together a story about a little-known 1920s gangster from Melbourne’s past. The period was a favourite with the readers of the community newspaper I worked for, and I enjoyed the research. It was fun poking about the city, searching in out-of-the-way places for undiscovered facts. Who knew what was around the next corner or down that narrow laneway? I found my imagination often took flight—it was reining it in that was the problem. Our budget was tight and our office tiny, and I knew I had to respect that stories about missing pets and the price of petrol were just as important as mine, even if in my heart I didn’t want to believe it.

I’d finished taking photos to go with the piece. North Fitzroy was full of tiny terrace houses where whole families had lived once, while the alleys behind them looked as if they hadn’t changed in a hundred and fifty years. My so-called gangster had hung out here, although these days it was difficult to imagine the grime and poverty of his everyday life. Rather than being the families of labourers and factory workers, crowded into the small rooms, the current residents were students and wealthy professionals flocking to embrace the inner-city lifestyle.

I climbed into my car—a second-hand white Fiat with malfunctioning heating—and buttoned up my green woollen coat, tucking my shoulder-length dark hair into a cream knitted hat. It was supposed to be spring, I thought grumpily, but there was no sign of it yet. My tote bag was on the passenger seat, and as I started the engine it fell sideways and my phone slid out.

I was reminded that I had to ring my mother. She’d left a message while I was interviewing an old dear about my gangster story, and when I’d tried to ring her back there’d been no answer.

‘Melody? I need to talk to you … I should have done it before, but … oh well, never mind. Ring me back as soon as you can. It’s about Anthony … Mr Maddox.’

It took me a moment to remember who Mr Anthony Maddox was. A recluse who lived at the Starburst Mine, about five kilometres outside my home town of Ironbark. He’d died back in July from a heart attack. Although a recluse, Mr Maddox did have the occasional visitor, and it was one of them who had found his body after it had lain undisturbed for at least a week. My sister-in-law, Freida, as the local doctor, had been called out by Constable Hugh Nicholson to formally pronounce death. It was one of the less pleasant tasks she had to perform. She wasn’t surprised though—while Mr Maddox hadn’t been exactly elderly, she’d said his heart was like a time bomb waiting to go off.

What was surprising was my mother’s message. ‘Anthony’, she had called him, as if she knew him well. Although Rain Lawson had lived in Ironbark for most of her life, and knew everyone and everything, I doubted she’d been friends with a recluse like Mr Maddox. I remembered her telling me she hadn’t been born there—she’d become a town local after her marriage to my father—but she may as well have been. Involved in everything, the go-to person for anyone in trouble, she was universally loved. As a personality she was warm and sensible and respectable. Sometimes, though, if something struck her as particularly amusing, she could let out a laugh that was almost raunchy. As if there was another woman inside that familiar exterior, wanting to get out.

Maybe she’d delivered some groceries to him? Taken him his medications? I could see her doing that, helping out. Just as she’d been helping out with the preparations for the Gold Hunt Weekend.

I’d been planning to go home for that. It was held on the last weekend in November, and my brother, Christopher, was running the show. I wanted to support him and the event, and it was nice to catch up with everyone, especially when these days I spent most of my time in the city. I knew, deny it though I might, that some part of me would always be a country girl. A tram rumbled across the intersection in front of me. I’d never get used to Melbourne traffic.

‘You could move back you know,’ my brother had said to me the last time I made one of my brief visits to Ironbark. Christopher being nine and a half years my senior meant we hadn’t been that close as children. Don’t get me wrong, I loved my brother, but sometimes he acted more like my father than a sibling. I used to wonder if the age gap would matter less as time went on, but now I was twenty-five and he was almost thirty-five, and nothing had changed. He was still bossing me around.

‘And how would I make a living?’ I’d responded, although we’d been over this subject before. ‘I’m a journalist. Ironbark has no newspaper.’ Then, because it had to be said, ‘Newspapers are a dying breed.’

‘Start one up, then! Or … what about doing podcasts? They’re all the thing now. Or take over the town website. You know I’m a dinosaur when it comes to technology. And there’s always plenty to do coming up to the weekend—we could use an extra pair of hands.’

These days, the Gold Hunt Weekend was what made Ironbark famous. Every year on the last weekend in November, the town celebrated an infamous hold-up by bushrangers, and visitors flocked in to search—in a tongue-in-cheek kind of way—for a chest of gold that had vanished over a hundred and forty years ago.

With a population of just under three hundred, Ironbark hadn’t changed all that much, although at the time of the robbery it had been dying. In 1874, the Cobb & Co coach had been the only thing that still connected it to the world, and the railway deciding to go through nearby Garnamulla had put paid to that.

Mrs Aurora Scott had owned Ironbark, more or less. At the time, she was a prominent businesswoman. Then the gold-chest-stealing gang of bushrangers swept into town and took her and several others hostage. The following day the police moved in to rescue them, but in the typical way of these things it went wrong, and there was a shoot-out. By the time the dust settled, Mrs Aurora Scott wasn’t there anymore. No one knew if she was dead or had run off. Or been forced to leave. She was just … gone.

As well as the Gold Hunt, Christopher ran most things in Ironbark. Our father, Jason Lawson, had been born in the town, and he’d had an inflated sense of civic pride. His son had inherited that as well as the pub and several other Lawson properties. I understood why my brother wanted to keep things going, and I was happy to help. I just didn’t want to immerse myself in Ironbark to quite the same extent as he did. Let’s face it, small rural towns aren’t that exciting, and I’d always had bigger dreams.

Going to university in Melbourne had been my first step in my escape plan. I could have stayed home—I’d almost bowed to the pressure I was feeling to stay—but my determination to expand my horizons had won out. Sometimes, growing up in Ironbark had made me believe I was suffocating. The town was small, everyone knew everyone else, and I was afraid if I stayed and made my life there I’d shrivel up and die. By the time I had finished high school I was desperate to throw myself into the big, wide world and experience all it had to offer.

After uni, when Christopher had asked me if I would move back to help out, I’d smiled and lied and said I’d think about it. But I believed that my future was here in Melbourne, and although my job didn’t pay much because newspaper budgets were tighter than tight, and I struggled every week to pay my bills, I still hoped that one day all that would change. I hadn’t always planned to be a journalist, but I’d fallen in love with the profession. At least in the city you could pick and choose what you wanted to be, while career choices in Ironbark had been so limited. I enjoyed what I did, mostly, but the trouble with my current life was that there never seemed to be enough time to actually sit down and consider my future. Sometimes whole months passed by in a blur, and it made me uncomfortable to imagine that in ten years nothing might have changed. Was I stagnating? As much as I loved writing my pieces, was it enough? When I had moved to the city it had seemed as if my choices were limitless, but these days I was beginning to wonder if that feeling of suffocation wasn’t just a small-town thing.

‘What about what’s-his-name?’ Christopher had asked. ‘Is he coming up for the Gold Hunt, too?’

What’s-his-name was no longer on the scene. He’d moved on to someone who knew what she wanted, unlike me, who was always searching for that elusive perfect relationship. I admitted to myself that, sadly, there hadn’t been anyone special in my life since we broke up six months ago. I’d told myself I was taking a breather, but I had actually started to worry about my poor choices when it came to matters of the heart.

‘I’m fancy-free again,’ I had said lightly.

‘You’ll meet the right man,’ my brother had said after a pause.

‘I think the right men are all taken.’

‘The wrong one, then,’ he’d joked.

‘Not everyone finds a soul mate,’ I had reminded him, still keeping it light. ‘You and Freida are special, you know that.’

I wasn’t jealous that my brother and my best friend had made a life together. I was glad for them. Everyone deserved happiness, it was just that some people found that contentment in their career and their friends rather than a tall, dark stranger. I was beginning to suspect I might be one of those people, and I told myself I was content, but the truth was it depressed me.

‘Hugh’s still single.’ Christopher had to have the last word. I heard the sly edge to his voice.

Hugh Nicholson, like me, had been brought up in Ironbark and now he was the law—the only policeman in town. Although we’d been good friends at school, and we’d even dated seriously before I went to Melbourne, it had ended messily. Our lives had taken different roads. I saw Hugh occasionally when I was in town, just to say ‘hi’, but I was sure he was as indifferent to my charms as I was to his. He was so much part of the community these days that his nickname was Constable Ironbark.

‘Hugh’s married to Ironbark,’ I had retorted, and changed the subject. My brother was worried about me. I’d had a string of short, failed relationships, and he thought if I came home he could keep an eye on me. It irritated me that he kept trying to get me back to Ironbark permanently. He didn’t seem to understand that having escaped once, it made no sense to come back. I’d outgrown my childhood home. Or at least that was what I told myself on those occasions when I lay awake at night, wondering what I was doing with my life. I wasn’t going to admit I might have been wrong, especially not to Christopher. I was just going through a rough patch, that was all. I’d sort it out.

Right now, I knew that November was a long way off, and I had plenty to do before then. I stopped at a red light on Johnson Street and thought about my gangster story. It was a good one and I asked myself whether the editor would let me run it over two weeks—all that interesting information, it would be a shame to cut it down to the bare facts. I also meant to explore the possibility of a podcast—Christopher’s idea had been simmering in my brain.

A woman with a pram hurried across in front of me just after the light went green. I slammed on my brakes, and my mobile phone sounded. My brother’s name flashed on the screen and I was tempted, but someone behind me tapped their horn, and I joined the slow stream of traffic. A siren sounded and we made way for an ambulance. My mobile continued to ring, but it still wasn’t safe to answer. I would be home soon, and Christopher would just have to wait until I got there.

The call cut off, and then it rang again, and again.

I glanced down and another horn blared. Anxious now, I turned down a side street and pulled over, and reached to answer.

‘Mel.’ Christopher’s voice sounded strange. I felt something in me drop away, and my hand tightened on the device. ‘Mel?’

‘Christopher? What’s wrong?’

‘There’s been a car accident,’ he said, as if the words were forced from him. ‘Mum …’ I heard the phone drop, heard murmurs in the background, and then, horrifyingly, Christopher was sobbing.

‘Melody?’ Freida came on the line. ‘It’s your mother. They’re taking her down to the Alfred in Melbourne. You need to meet her there. Don’t wait. Go now.’

Brothers of the Vine

Brothers of the Vine Forever Evermore

Forever Evermore Women of W.A.R.

Women of W.A.R.