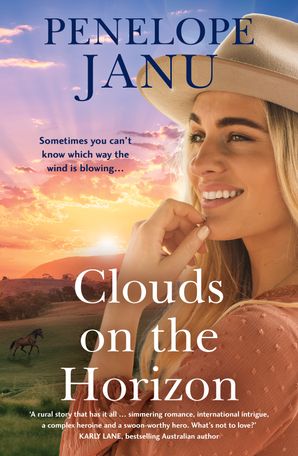

‘A rural story that has it all … simmering romance, international intrigue, a complex heroine and a swoon-worthy hero. What’s not to love?’ Karly Lane, bestselling Australian author

Will a misunderstanding and past trauma stand in the way of profound attraction? Immovable determination meets irresistible charm in this delightful rural romance from an award-winning and much-loved author – for readers of Rachael Johns, Karly Lane and Fleur McDonald.

When Phoebe Cartwright finds Sinn Tørrissen, a naval officer and meteorologist, frozen half to death in the middle of a thunderstorm, she believes she’s saved his life. Sinn, unfailingly competent and infuriatingly arrogant, disagrees. In Phoebe’s small country town to track down the members of an illegal horse-racing syndicate, the last thing he needs is to become entangled with Phoebe.

A much-loved member of her community, the prickly and independent Phoebe is used to solving other people’s problems. So when she learns her younger sister could be implicated in their father’s dishonest accounting for the syndicate, she insists on working with Sinn to uncover the truth.

Sinn is both confused and entranced by the passionate Phoebe and in spite of her resistance, Phoebe finds herself drawn to him. But Phoebe is determined to protect her sister above all, and the secrets she cannot tell Sinn threaten to sweep his investigation – and their romance – way off course.With clouds building on the horizon, can Phoebe and Sinn weather the gale and find in each other a shelter from the storm?

‘Encapsulates everything I love about the romance genre and so much more. A go-to author for rural romance for the head as well as the heart,’ Joanna Nell, Bestselling Australian Author

Stripes of silver hang in the air and rivers of water crisscross the track, but Camelot, black as the clouds, treads confidently over the uneven ground. Leaning forward in the saddle, I stroke his rain-soaked neck. I breathe in eucalyptus and the dampness of the earth.

My face is wet, as is the hair that’s come loose from my plait. Between the tops of my knee-high boots and the leg flaps of my oilskin coat, my jodhpurs are sodden. I run a finger inside my collar and re-fasten a press stud, shivering as we skirt around the tree roots. Notwithstanding my gloves, pins and needles prickle my fingers as I clench and unclench my hands. When I push Camelot into a trot, my body warms, but the wind is cold on my cheeks.

Camelot, as happy as a platypus swimming in a stream, breaks into a canter at the top of the rise, and I laugh as I pull him back. ‘Not today, boy.’

A rumble of thunder sounds in the distance as we pass Mr Riley’s shearing shed and sheep pens. The water tank is shrouded in mist.

When Camelot shies, edging off the path and into the bush, I increase the pressure on my outside leg to bring him back to the track. He complies but tosses his head as I guide him towards the copse of gums and the narrow dirt road that leads to the churchyard and home. He shies again, skittering sideways. I steady him, patting his neck, when he takes a tentative step.

‘What’s the—’

A long dark shape lies across the track, blocking our path. I kick my feet free from the stirrups and slide to the ground, my heart thumping hard. I bring Camelot’s reins over his head and loop them through my arm.

The man lies on his front with an arm thrown out to the side. One of his legs is bent at the knee and the other is straight. His pants are dark; his white shirt sticks to his skin. Kneeling at his side, I touch his shoulder. Even through the rain, my gloves and his shirt, I feel his body stiffen.

He spins and rolls onto his back.

‘Oh!’ I sit back on my heels.

He’s in his late twenties, maybe early thirties. He has a straight nose and a strong jaw. Blood trickles from his temple to his ear. ‘Hvem er du?’ he whispers.

I lean over him. ‘What?’

He’s shivering so hard that his whole body trembles. His eyes flutter closed. ‘Who are you?’

‘Phoebe. Who are you?’

His eyes open again and he blinks as if trying to focus. ‘Phoebe Cartwright.’

‘How do you know that?’

He lifts an arm and drops it. He shakes his head. With a shuddering exhalation, he passes out.

I pull off my gloves and rest my fingertips against his neck, counting carefully through the fear that tightens my chest. His pulse is faint. Breathing laboured and shallow. Skin cold and pale. Sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell. It’s my job to know about the senses, but this is beyond me.

When his eyes spring open, I jump. ‘Telefon,’ he mutters.

‘There’s no reception here.’

He’s cleanly shaven. His thick, dark hair looks recently cut. He’s wearing a business shirt and suit pants. His shoes are city shoes, leather with narrow eyelets and long thin laces. Why is he in the middle of nowhere, alone and icy cold?

How does he know my name?

I touch his cheek and he flinches. ‘Who are you?’

He shakes his head. ‘No.’

‘You’ve bumped your head. You’re freezing. Tell me your name.’ He utters a string of words I don’t understand. Danish? Swedish?

I think it’s Scandinavian. Another shudder takes over his body. He stares at me and swallows. ‘Get my phone.’ He lifts his hand, but just like before it drops back to his side. ‘Find it.’ His voice disap-pears but I read his lips. ‘Pocket.’

‘We have to get out of the rain.’ I look towards my home, a kilometre away. And then I look up at my horse. Now that the shape on the path has taken human form, Camelot is curious. When he lowers his head, only half the length of the rein separates us.

I turn to the man again. ‘I don’t suppose you can ride?’

‘Motorsykkel?’

‘A thoroughbred.’ By the time I indicate Camelot behind me, the man’s eyes have drifted closed again.

He shakes his head. ‘No.’

‘I don’t think you could get onto him anyway. Can you stand? Can you walk?’

His eyes open and his brow creases, as if he’s considering my questions. And then, as if in slow motion, he rolls onto his front. He moans as he comes up on his hands and knees. He’s slender but his shoulders are broad. The muscles on his arms and chest are clearly outlined through his shirt. I’m average in height, but there’s no way I could carry him. I don’t think I could drag him either.

Mr Riley hasn’t sheared in his shed for years, but he keeps winter hay, tools and other paraphernalia here. It’s likely to be weather-proof and even if it isn’t, it’ll be safer than being outside. I put my hand on the man’s shoulder.

‘There’s a shed twenty metres away. We can go there. Other-wise, I’ll have to ride home and call an ambulance on the way.’

‘Telefon.’

A bolt of lightning splits the sky and thunder breaks it open. ‘That settles it.’ Getting to my feet, I take hold of the man’s arm with both hands and pull as hard as I can. ‘You have to help. You have to stand.’

It takes a minute at least for the man to get off the ground. I pull his arm around my shoulders. Even stooped over, he’s tall. When Camelot nudges my back with his nose, I stumble.

‘Cut it out, boy.’

‘Telefon,’ the man whispers, as blood drips on his shirt. Another bolt of lightning, closer than the last.

‘Why won’t you tell me your name?’

‘Nei.’

I don’t know what he’s up to or where he’s from, but he’s far too weak to cause trouble. I adjust his arm over my shoulder. ‘Let’s get out of the storm.’

When I take a step, the man stays rooted to the spot. He holds out a hand and Camelot sniffs it.

‘Vakker hest.’

He speaks nicely enough, but I have no idea what his words mean. When he sways towards Camelot, I pull his arm more tightly around my shoulders.

‘You have to walk.’

Leaning so heavily on me that I’m forced to brace my legs to stay upright, the man takes slow, leaden steps to the shed. Camelot, his footfalls soft on the rain-soaked track, walks patiently behind us.

The shed isn’t locked, but the bolt is stiff and I can’t work it while supporting the man. I balance him against a wall. ‘I won’t be long.’

A moment after I release him, his knees buckle. I shove my shoulder against his chest to support him as he slides to the ground and slumps against the wall, his head tipped onto his chest. Another flash of lightning illuminates the bolt, but even two-handed I can’t pull it back, so I rifle through the grass and find a brick. I whack the curved end of the bolt until it slides clear of the barrel. I pull against the doors and they swing outwards. The shed smells of hay, wool and dust and it’s even gloomier in here than it was outside. Camelot baulks at the doors, but after I double back and pat his rump firmly, he walks tentatively over the threshold. When I loop his rein through a sheep pen on the far side of the shed, he stares back with big black eyes.

By the time I return to the man, he’s facing the wall, pressing both hands against it as he works his way up. He leans on me as we inch towards the shed, but when we get to the doors, he reaches out and grasps the frame. He looks inside. Sways.

‘Nei.’

‘Yes!’

When I push him through the doors, he staggers towards a stack of hay bales, dropping to his knees just before we get to it. The doors crash shut, plunging us into darkness.

A whimper works its way up my throat.

I swallow compulsively, stilling the memories, the old, relentless fears.

‘It’s not locked,’ I say aloud, my voice thin and high.

My eyes adjust. The windowpanes are filthy but rain streaked. I can see the outlines of gum trees through the glass. Light filters through the six half-doors behind the shearing platform. Shearers would have pushed freshly shorn sheep through the doors to scramble down the ramps and quiver in the pens.

I can breathe.

Camelot’s bit jangles. When he shifts a leg, his shoe scrapes the concrete. I make out a stirrup iron, glistening dully in the darkness. Another gust of wind rattles the doors on their hinges.

I can get out.

I step carefully to the doors and push them open, ignoring the gusts of icy wind and rain as I kick the half-brick under one of the doors, creating a wedge. By the time I get back to the man, he’s flat on the concrete. Concussion? Hypothermia? Either way, he has to warm up. Dragging six bales of hay off the stack, I lay them out like a bed.

‘Can you get up there?’

He doesn’t have the strength to stand, but I yank until he kneels and, pushing and shoving, roll him onto the bales. He lies on his back, groans and loses consciousness again. My hair sticks to my face. Rain or sweat? When I feel for his pulse, even weaker than it was before, I see a card through the pocket of his shirt and slide it out. The cardboard is wet through but the words, black on white, are clear enough.

United Nations First Committee

(Disarmament and International Security)

Sindre Tørrissen

He doesn’t have a title, but the string of initials next to his name suggests scientific qualifications. There’s a UN email address and two telephone numbers.

‘Sindre?’

His eyes briefly flicker open. ‘Sinn.’

Whoever he is and wherever he’s from, he won’t warm up if he’s wearing wet clothes. My fingers are stiff and clumsy as I pull his shirt free of his pants. After I fumble over the top two buttons of his shirt, I grasp the front panels to rip the remaining buttons through the holes.

‘Sorry about that.’ I undo his cuffs before rolling him onto his side to pull off the shirt, then push him onto his back again. Thunder rattles the roof and lightning brightens the shed. His chest is firm, his abdominal muscles clearly defined.

When I exhale, my breath is white. ‘Your pants are wet too.’

I peel off his socks and tug at his shoes. I undo his belt buckle and button, and unzip his fly, exposing his underpants. ‘I’m not look-ing. I promise. And those can stay on.’

I focus on the hay as I pull off his pants, dropping them onto the pile with his other wet clothes.

Opening the press studs of my oilskin, I shake off the worst of the moisture. I pull the man onto his side, spread the coat out behind him and, brushing off the hay that’s stuck to his skin, roll him onto the coat. I draw the thick cotton lining around his body. The coat covers most of his legs and torso, but isn’t wide enough to wrap around his chest, so I take off my sweater and smooth the wool, warm from my body, from his waist up to his neck. I gather the coat around his sides. A drip from his hair rolls down his cheek, joining a trail of blood trickling across his throat.

Taking off my T-shirt, I fold it in half and rub his hair, shivering when drips fall from the end of my plait and down my spine. He blinks.

‘Du er vakker.’

‘I can’t understand you,’ I say as I hastily pull my T-shirt back over my head. The fabric is damp. I shiver again and rub my arms. ‘I’ll see what else I can find.’

Camelot’s saddle blanket is warm and mostly dry. I remove his saddle and rest it over a railing before wrapping the padded rectangle around the man’s feet, tucking it under his heels to secure it. I frantically search the perimeter of the shed before finding a stack of hessian sacks on the shearing platform. They’re clean and thick, rough against the insides of my arms when I pick them up. I shake them out and layer them on top of the man, then I free the cape of the oilskin from under his shoulders, lift his head and lay a folded sack beneath it, positioning it like a pillow.

He’s trussed up like a mummy, but he’ll be warmer. So why, all of a sudden, is he so frighteningly still? Shivering is the first stage of hypothermia. After that, the body preserves energy for the vital organs—the lungs, heart, brain and kidneys. I burrow through the sacks and coat and touch his side. His skin is as cold as marble. I search for the pulse at his throat but can’t find it.

‘Please don’t—’

Available in-stores and online from the 5th of January 2022

Brothers of the Vine

Brothers of the Vine Forever Evermore

Forever Evermore Women of W.A.R.

Women of W.A.R.