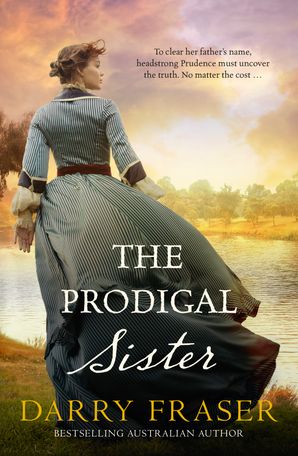

Headstrong Prudence North faces a dangerous blackmailer who threatens her family and her dreams of escaping domestic drudgery. An enthralling historical mystery from a bestselling Australian author.

1900, Melbourne, Victoria

Miss Prudence North is freshly returned from university in Scotland and determined to find her place among the male-dominated world of the new forensic sciences when a high-ranking policeman waylays her. He threatens to charge her father for illegal medical practices unless she helps him build a case against local landowner Jasper Darke by spying on him.

With her sister’s illness worsening, if their income disappears, Prudence will have to take on nursing and domestic duties and she’ll never have the freedom she craves. Prudence has no choice but to agree.

Immediately taken with the handsome Mr Darke, a seemingly good and honest man, Prudence can’t see what nefarious activities she’s meant to be reporting on. She’ll have to get closer…

But when a body turns up at her father’s surgery, the forensics reveal to Prudence there’s more going on about all this than meets the eye. It’s clear it’s up to her to uncover the truth – of this murder, of whatever’s going on at the surgery after hours and, especially, of the intriguing Jasper Darke. Her life, her family and her future rely on it.

Melbourne, 1900

Prudence North snatched her arm from the young constable’s steely grip.

‘Sit, miss,’ he said, his tone gruff, his eyes darting in the dim light. He shook a finger towards three chairs around the only table in the middle of the stuffy room.

Too big for your boots, mister. Indignant, she tested for the least soiled, least rickety of them. What sort of muck would need to be cleaned from her dress? Not happy, she sat on the dirty upholstery of one that faced the door. Not. Happy.

Weak shafts of sunlight filtered through the mildewy window, drawing attention to the oily, dust-caked splotches on the table. Dingy. Hardly conducive to calming the nerves.

‘Mr Bankston won’t be long,’ the man said sharply. He pulled the door slightly ajar and couldn’t get out fast enough as he slid through the barest opening. The door shut loudly and ominously. A thin stream of cool air had managed to slip inside but did nothing to cut the thick fustiness.

Her heartbeat was throbbing in her head as she waited. The room—the interview room she’d been told—was nothing but a shabby structure out in the yard somewhere behind the main buildings. And not for the faint-hearted: the whiff of vomit and other effluvia hung in the stale air.

Earlier, two officious, arrogant young constables had arrived at her home insisting that she accompany them quietly to the Bourke Street West police station.

‘On Mr Bankston’s say-so, miss. No nonsense now. Come along.’

She couldn’t think what would incline Mr Bankston, a family friend, to treat her this way. As if I was a street woman, for goodness sake.

‘What’s all this about?’ she hissed.

Her appeal had fallen on deaf ears. She’d had to make a rushed decision then not to worry her mother and her mother’s nurse, Mrs Kirby. And so she’d shouted a goodbye, grabbed a little purse, her hat and gloves and hoped her haste would satisfy the impatient police.

Her father wasn’t home. He’d already driven the buggy to the street for supplies and had taken her sister Valerie with him. It was to be a short outing. Melbourne air could not be considered ‘fresh’: with all the horse manure, the coal and wood fires burning, and despite new sewage works, effluent was still on the nose. The city lived up to its unkind but apt nickname, Smellbourne.

Had Mr Bankston known that she’d be almost by herself at home? Her nerves had rattled and then an odd dread filled her, though she couldn’t think why.

Both constables, similar in size (underfed, and a little taller than she) and age (probably early twenties), had been stoically silent (under orders, no doubt) in the driver’s seat despite her shrill demands for information. Inside the unmarked carriage she’d hammered on the wall—she had not gone quietly.

They finally arrived in the city west district, which was miles from her home in Jolimont, and drove into a carriageway along-side the muted Gothic red-brick construction of the police station. There they herded her over a small lane and via a back door into this otherwise empty yet menacing place. It might have intimidated a lesser person. Nevertheless, the room had a palpable derision for the ‘innocent until proven guilty’.

Apprehension tingled. She eyed the grubby table in front of her and her lip curled. The grime there declared its contempt for those who had the misfortune to sit at it.

Hinges creaked as the door opened and welcome light filled the room. Mr Bankston entered, almost casually, and gave her only his nod of recognition. His coat-tails brought with them a chilly rush of air, offering no reprieve in the dense space beyond him. Mr Bankston closed the door with a firm hand.

All business, no friend of the family now it seems. A high-ranking police officer, there was no drab uniform for him like others in the force. Underneath the morning coat, he wore a vest and trousers in charcoal wool. And his shoes were highly polished black leather—an older pair well creased, nonetheless impressive.

Apparently, he was second only to the Chief Commissioner, Mr Chomley. Prudence couldn’t attest to the veracity of that claim, even though he’d been known as such to her father for many years. Mr Bankston removed his gloves and tucked them in his coat pocket. Perhaps he was now a detective, or some sort of special investigator. She had been away studying in Scotland for some years until very recently and had not caught up.

‘Good afternoon, Miss North.’

‘Good afternoon. What—’ He held up a hand at her raised voice and, surprised, she stopped briefly before she testily began again. ‘I’ve been marshalled without explanation to Bourke Street West, by your men, into a building not even the police station itself, to be interviewed by a so-called family friend. What on earth is going on?’

He sat opposite (rickety chairs no bother to him). ‘I make no preamble. Dr North, your father, is accused of engaging in criminal activities in his medical practice,’ he stated, as calmly as you like.

Shocked to silence, she stared at him. Clutching the purse on her lap, her fingers became painfully tight around the few coins and handkerchief inside.

‘And that, you see,’ he went on, his gaze holding hers, ‘puts me in a predicament.’

He sounded his normal pleasant self, only this time the dulcet tones were a little foreboding.

Under the pale sunlight that illuminated the room, his hand-some face, usually affable and open, was now closed. His dark hair shot with elegant streaks of silver made him look rakish. His heavy brows had knitted, and his dark eyes held a level of concern—not for her, but for his predicament, no doubt.

Thoughts raced through her. Everard hadn’t referred to her father by his first name. Unusual. Being a close family friend allowed him certain privilege. Why, four years ago in the weeks just after she’d arrived in Scotland, he’d even written to her asking about her studies at the University of St Andrews. An interested family friend.

He sighed. ‘I take your silence to mean I may continue?’

Letting go of her purse to straighten her only good woollen jacket and tug at the sleeves, she said, ‘How so a predicament, Mr Bankston? You of all people can substantiate my father’s character.’

Tilting his head a little, he said, ‘You used to call me Everard.’ He laced his fingers, rested his hands on the grime.

Anger simmered as she swallowed down gulps of fetid air. ‘You used to call my father Gregory, and me Prudie. Perhaps the very nature of this interview abandons such familiarity,’ she snapped, which didn’t relieve the nerves that skittered through her.

He leaned forward, and the cuffs of his jacket planted on the mucky table. His nose twitched—clearly he wasn’t immune to the smell in the room. What was he thinking, ordering her here?

‘I will have to suspend your father’s practice until the charges are cleared.’

Charges?

A distressed wail reached her ears, from out of nowhere, and made her flinch. Were prisoners close by? Were there cells here? The gruff shouts of men sent her stomach aflutter once again.

‘What charges?’ She sounded shrill.

He ignored her. ‘Miss North, it is a grave matter. I’m aware that Gregory has been under a great deal of pressure lately—’

‘How would you know that?’ she shot back, rightly or wrongly, unable to keep her temper in check any longer. A rise of triumph at the fleeting irritability that crossed his features gladdened her.

He gave a snort. ‘Perhaps I know more than you since you’ve only been back in the colony three weeks.’

Oh—it isn’t his place to make a rebuke. But she shifted in her seat. There was nothing wrong with following the dream of further education, spending long years away to do it. Her mother and father had always encouraged—

‘I do know,’ he went on, his gaze flinty, ‘that your mother’s health is now severely compromised, and that your sister, Valerie, has begun to show the same affliction.’

Prudence’s mouth pinched and her chin wobbled a moment. The affliction had only been named in 1872 by a young American, Dr George Huntington, though she knew it had been documented before then. This degenerative, incurable, inherited disease that cruelly keeps stripping a person of physical and mental abilities.

When Prudence had left for Scotland, her mother hadn’t been anywhere near as debilitated as she was now. On her arrival home, she soon learned from her father that for the last few years he’d confined her mother to the house, hidden from all visitors except for the faithful nurse, Mrs Kirby. He said it saved her from the dreadful response society had to the illness.

And Valerie had been so vibrant back then. Her features were all their mother’s—cherubic blonde curls, pouty cherry red lips and blue eyes set deep in an oval face. There had only been small signs in her sister when Prudence left. Now she was lacklustre, and her speech was slurred on occasion.

Prudence, so different to her mother and sister, resembled more her father’s side of the family: she was dark-haired, not a natural curl in sight, of medium height—a good few inches on her mother—and with features that echoed a Mediterranean influence (ancient family history no doubt, her father had said). She had the aquiline nose, the same warm brown eyes of her father, high cheekbones and skin that easily turned a shade darker and freckled if she ventured into the sunlight without adequate cover. Roman girl, her sister would tease.

Oh, Valerie.

Mr Bankston (she would not refer to him as Everard now) went on, spread his hands before replacing them on the table. ‘Your father is desperate. I’m sure he wishes to find a cure and to care for them both. It’s why he called you home, isn’t it?’

‘An awful coincidence.’ She cleared her throat. ‘You know I was lodging with my uncle John, a clergyman, and his family in St Andrews to study at the university.’ She sighed. ‘They were only renting so when he died three months ago the family had to move away.’

Her aunt had made it quite clear that Prudence wasn’t welcome to go with them. (Aunt Aggie had never been warm to her.) So she’d applied for residence in the University Hall for Women, which would’ve enabled her to continue her studies.

‘About that same time, Papa’s letter called me home, so I boarded a ship as soon as I could.’ Thanks to the speedy steam-ships shortening what had once been a long and tedious journey to Australia, she arrived home in just over forty days—every day spent hoping she’d be in time for her mother, and she had been. Three weeks home now, after a relatively easy crossing spent with a pleasant married woman as a cabin companion.

Prudence sent him a brave glare. ‘Mr Bankston, whatever you might think my father has done at the clinic’—he gave her a dismayed look, shook his head—‘it would not be because he is desperate to care for his family.’ She sat straighter in the seat. ‘And I know that the law cannot charge me, or hold me, for alleged crimes attached to another’s name.’

Mr Bankston leaned back in his chair. It squeaked but he was unperturbed. A lean man, his bearing was casually assertive. He had a confident grace, which on earlier occasions, she’d admired, and had sometimes wondered—

‘Of course not. You’re right,’ he said, nodding and assessing her. ‘I certainly can’t do that, nor would I wish to charge you on any occasion.’ His tone dropped as his brow furrowed. ‘In fact, it pains me that you think I, your friend, would attempt such a thing.’

Oh, no familiarity now, thank you. ‘It pains me that I’m here at all.’ Ignoring the twitch of his eye, she continued, her voice tight. ‘It’s monstrous to believe that my father has supplemented his income with illegal practices. He’s not wealthy but nor is he a criminal. He needs his work. You should know that. Besides, now I’m back, things at home are being better managed.’

She’d been relegated to home duties at first, assisting their housekeeper, Mrs Kirby. Not that she objected to looking after her mother and sister but soon, now that she’d established a better process for the family, she would seek a paid position outside the home. As it was, her father had already coaxed her to help out at the clinic.

Mr Bankston put his elbows on the dirty table, his clasped hands in front of his mouth. ‘Miss North, I’m not trying to be some sort of fiend.’ His eyes had become bleak. ‘I need your help.’

Prudence scoffed while looking about the room at the dirty walls, and the only window smudged with what she imagined was years and years of airborne muck. Why was she in this room and not in the station proper? He must have thought her a fool. Something else was bothering her.

‘And why aren’t other police around, going about their business? The place should be buzzing with men.’

‘We’re in here because it’s a delicate situation. There are few to be trusted with it.’

He was serious. Was this what detectives did—undertake clan-destine interviews to glean information? ‘If it’s some rich creditor after him, which I find highly unlikely, I’ll find work and pay whatever debt you’re trying to tell me he owes.’

Bankston sat back, rubbed his forehead a moment. ‘He’s no longer to practise at all. Do you understand? I can’t allow it.’ His voice was hard and very low.

‘Rubbish. He’ll still go to work every day.’

He shook his head. ‘He might leave the house for a short while every day.’ A hand flattened on the table. ‘He’s in trouble. You need to think not just of yourself, Prudie.’

Another rebuke, and put so bluntly, it stunned her to silence once again.

‘I need your help,’ he said once more, quietly insistent.

More confused now, she blustered, ‘What help? What help could I possibly offer the police?’

‘It’s a sensitive operation.’ He sighed, his eyes tired. ‘I know you were interested in extraneous studies while you were in Scot-land. Isn’t that the reason why you didn’t enrol here in the Uni-versity of Melbourne?’

The change of subject startled her. Where is this heading?Police work had always interested her; not the sort that hauled some poor sod off the streets but work of the detective kind. Women were discouraged to study such things—although it was slowly becoming available to them at certain colleges and universities, few and far between.

Not quickly enough, damn and blast it.

She’d undertaken a Master of Arts, which at least these days was equal to a man’s degree. Up until six years ago she’d only have been able to undertake a Lady Literate in Arts diploma. Even though older than other graduates at the time she’d enrolled, she was glad she’d waited to study in Scotland. Hopefully now, here at home, she could spread her wings into science.

‘Prudie?’ He was waiting expectantly for her answer.

‘One of the reasons, that’s true. A new science of investigation developed in France, called forensics, is very motivating.’ She stopped there, suddenly wondering if he was merely patronising her with his attention.

‘Go on. I’m interested to hear.’

Although not sure of that, she did continue. ‘M’sieur Lacassagne, for years a practitioner of forensic medicine in his school of criminology, has had wonderful results. And not only that,’ she said, warming to her subject, ‘fingerprint identification is being accepted, so much so that a branch at New Scotland Yard will open.’ She paused, enthusiasm loud in her own ears. Oh, such exciting things that will help unravel the mysteries of murder and mayhem.

She’d asked her father to write to France for copies of Lacassagne’s papers—a request better coming from a medical doctor, a man—and hoped they were not too far away.

‘I see. Quite a lot to take in.’ Shifting in his seat, he looked at the palm he’d just landed onto the dirt of the tabletop then at the pads of his fingertips. Reaching into his coat pocket, he pulled out a large handkerchief and wiped both hands then dropped it to a spare chair alongside him. ‘Your father had told me how proud he was that you’d followed up your interest in crime detection.’ He gave a little smile, cool and superior. Patronising.

Heat rushed to her cheeks. While generally speaking, a woman was discouraged from having such an interest in so-called male-only intellectual pursuits, she had thought him far more advanced than to demean her. Despite the outmoded thinking, women had already moved into certain scientific fields—medicine was one notable domain—and showed equal aptitude for the work that couldn’t be denied.

Her father thought she might have taken up medicine and perhaps follow in his footsteps, hence his coaxing her to assist him. He was a great advocate of the work of Joseph Lister and before him, Louis Pasteur, and took every opportunity to practise and preach their hard-fought antiseptic theories. It reminded her that she must wash her hands thoroughly after being in this disgusting room.

She clenched her hands in her lap. ‘You might be interested to learn,’ she said, her temper in check, her sarcasm in full flight, ‘that my gender precludes my studying in the field at present.’ Of course he would know that. ‘So I fail to see why I’ve been escorted to this filthy place for my interest in what’s considered only my hobby.’

His brows raised. ‘I don’t believe it is a hobby for you, and even if that were so, I’d like to give you the opportunity to use your skills.’

The Prodigal Sister by Darry Fraser will be available in-stores and online from the 1st of December 2021

Find it here

PRAISE FOR DARRY FRASER:

‘Darry Fraser has proven yet again that she is a master at writing Australian historical fiction … The Last Truehart is an enjoyable and well written tale – a great yarn, a dashing hero and a real sense of place in the evolution of Australian society of the time.’ – Great Reads & Tea Leaves

‘Darry Fraser effortlessly weaves historical events throughout… a must read for historical fiction fans.’ – The Burgeoning Bookshelf

‘A fabulous storyteller who underlies this compelling plot with strong female characters who challenge the status quo…Fast paced historical fiction, first-hand experience of the South Australian landscape, and the added bonus of a plot line that has been drawn from Darry Fraser’s very own family history make this an authentic, seamless and riveting tale.’ – Better Reading

Brothers of the Vine

Brothers of the Vine Forever Evermore

Forever Evermore Women of W.A.R.

Women of W.A.R.