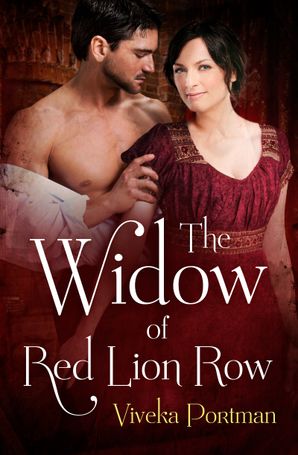

In the slums of London, she’ll do almost anything to survive …

London, 1810. Margaret Forsythe never expected to become a condom maker. But she is a widow, and due to her late husband’s careless will, she has lost everything. Now she has been exiled to the filth of Southwark, with no money or means of survival.

Never again will she be beholden to a man. But when her situation becomes dire, she has little choice but to throw herself on the mercy of the dangerously handsome brothel owner, Charles Grimsby.

Charles’s prostitutes need condoms (or ‘johnny caps’) to avoid venereal disease – and so, torn between morality and poverty, Margaret begins to manufacture them, using animal gut and ribbons. Will this new enterprise be her salvation, or her ultimate ruin?

Chapter 1

St Saviour’s Cemetery,

Southwark, London, January 1810

Mrs Margaret Forsythe watched dry-eyed as the gravediggers lowered her husband’s coffin into the hard, frozen earth. The churchyard was bleak, and precious few had gathered to brave the cruel weather to farewell a man largely disliked by all who met him.

Fool man.

The thought was uncharitable on this day of all days, yet still remained true.

Margaret clutched her bonnet to her head as a wicked gust of icy wind threatened to whisk it away altogether. Her silvering hair tore from its pins and whipped her cheeks.

The vicar said a few more words, but she didn’t hear them. Her mind whirled with the wind in her skirts and her brow furrowed in fury. She looked up towards her brother-in-law, Mr Samuel Forsythe.

If it were possible, she hated him more than she hated the fool of a husband resting in the ground. Ruddy red cheeks, slack ugly jowls and a noticeable trickle of snot shone in the grim daylight just above his lip.

Repulsive. Stupid. Cruel man.

Mr Samuel Forsythe nodded with pomp and an embarrassing lack of humility at the thin vicar shivering in his robes.

‘Thank you, Vicar. My brother would have welcomed your kind words.’ His gratitude was dismissive.

The thin vicar inclined his head, and looked expectantly at Mr Forsythe.

It was custom to offer the vicar some coin in exchange for his Holy service, but Margaret’s brother-in-law’s hand remained firmly in his coat pocket.

Humiliation gripped her belly, and Margaret found her own hand delving into her reticule to extract the meagre coinage there.

‘Father, here,’ she said softly, carefully stepping over the frosted ground to press several coins into the vicar’s frozen hand.

It wasn’t much, Margaret knew, but she could no longer afford to offer him any more.

The vicar’s expression faltered in surprise as he opened his palm to observe the paltry sum of money for his services on this day, but he recovered swiftly and inclined his head graciously. ‘Every little bit will help the church. My thanks, Mrs Forsythe, and my condolences on your loss. Your husband is truly in a better place,’ he murmured.

Yes, but what a place he has left me. The thought was bitter.

Margaret didn’t miss the vicar’s dark look accusingly thrown in the direction of her brother-in-law, who was already turning to make his way towards his carriage.

With a regretful shake of his head, and no further farewell, the vicar turned, clearly eager to return to the crumbling St Saviour’s Church and be out of the weather.

Another bitter gust of wind rushed around Margaret as she stood, now alone beside her husband’s grave as the unfortunate diggers covered the remainder of the grave with clumps of hard, un-giving earth.

Never again, she told herself. I will never marry again.

A horse whinnied softly, and Margaret turned to see Samuel Forsythe and his wife climb into the relative warmth of their carriage, without even so much as glancing at her.

She started towards them.

The door to the carriage clicked loudly shut, and Samuel reached over and began to draw the curtain over the window.

Surely they wouldn’t leave her here? Certainly he would return her home?

‘Mr Forsythe!’ Margaret exclaimed. ‘Wait.’

Samuel’s head turned, his thin lips curled in a smirk. Slowly and deliberately he shook his head, and tapped the window, urging the driver to depart.

Margaret tried to run and stop him, but it seemed in horror, her legs turned to ice.

‘Samuel …’ she called, alarm making her voice shrill. Again, she tried to force her legs into motion. Stubbornly, they refused.

The driver, her old driver, Mr Peacock, turned and shook his head pityingly. He was hunched in his coats, water dripping from the wide brim of his hat.

‘I’m sorry, madam,’ he muttered. His head lowered with shame. ‘I …’

‘Mr Peacock …’ Margaret gasped. ‘Please … Don’t leave me here!’ She gestured to the all but barren churchyard in desperation.

She could see the older man wince at her plea, then wince again when Samuel rapped impatiently once more on the window.

He shook his head again. ‘I’m so sorry.’

There was nothing he could do without risk to his employment, Margaret knew that. Samuel would surely dismiss him if he allowed her onto the carriage. All common sense told her this, but his rejection still stung.

The horses whinnied again as Mr Peacock reluctantly urged them away into the smoky haze of Southwark, to cross the Thames and return to the house that had once been hers.

For a good long moment she stood before her husband’s grave, frozen and lost.

Rational thought told her Mr Forsythe’s hasty departure was to be expected. He owed her nothing now. According to law, her husband’s heir was his brother, and Samuel Forsythe had inherited everything.

Unfortunately for Margaret, she and her husband had no sons to inherit her husband’s wealth and property. Their daughters, both as cruel and unfeeling as their father, were well married and living in the country, without need for further assistance or dowry. It left Mrs Margaret Forsythe at the age of one and forty at the unenviable mercy of her brother-in-law’s dubious sense of chivalry and generosity.

Stupid, stupid Roger.

Honestly, her husband was a born fool, and a fool without any foresight at that.

Despite her husband’s accountant’s sage and frequent suggestion that he write a Last Will and Testament to ensure his brother provided generous financial maintenance for his widow should he die, Roger had sneered it off. As Roger often did.

So, when Mr Roger Forsythe had died unexpectedly of ague one week ago, Margaret’s misery had been compiled by the discovery that her future care and maintenance was firmly in the hands of her brother-in-law, Mr Samuel Forsythe, a man who held no affection for his sister-in-law, nor indeed any other living creature, so far as Margaret was aware.

Still, as society expected, Mr Samuel Forsythe had very begrudgingly provided some allowance for the newly widowed Margaret. He had ungenerously offered her a meagre allowance of thirty pounds a year and moved all her belongings from her lovely terraced house in St James’s Street, and handed her the title to one of her husband’s run-down investment properties in Red Lion Row, Southwark.

A tiny, terrible and smelly terrace set amongst the tanners, gaming hells, opium dens and slums of south London.

She was luckier than some, she supposed. She could have been left nothing at all.

Men were greedy, cruel creatures. Ruled by lusts for money and women. Roger and Samuel Forsythe were no different. She gazed at the black soil surrounding her husband’s grave, as black as the bruises he’d occasionally given her. She winced as the wind cut through the layer of the cloak.

Never again, she swore.

Never again would she willingly put her life in the hands of another man.

‘You all right, madam?’ a soft, almost shy voice startled Margaret from her unhappy reverie; she turned to see one of the gravediggers approaching her. She gripped her reticule tightly.

His eyes were dark brown, almost black, shadowed by the gloomy smog and the short brim of his hat.

‘I …’ Margaret hesitated.

Am I all right? she wondered.

Indeed no.

A light drizzle began to fall.

The gravedigger waited for her halting response. He was wearing old and dirty clothes, his boots were nearly worn through, and were smudged with grave dirt.

I wonder how long it shall be until my boots wear as thin?

The thought was unpleasant and sad. Samuel’s paltry allowance would scarce feed her and a maid, let alone buy her new boots each winter as she was accustomed.

‘I don’t quite know,’ she answered after a moment. ‘I seem to have been left.’

It was true, wasn’t it? She did not even know the way to Red Lion Row.

She watched the man for his response, he could molest her here in this lonely churchyard, and no one would be the wiser.

A thin coil of fear began to grip its way around her chest and tighten about her throat. She stepped away, a shiver creeping up her spine.

The gravedigger’s eyes grew kind and sympathetic.

Tears sprung into her eyes; she hadn’t expected that.

‘I’m sorry for your loss,’ he said and took his hat off and inclined his head. ‘Where you headin’ then, madam?’

‘I have a place in Red Lion,’ she spoke so softly, a hot blush rearing up her neck, ‘but I …’

The man didn’t allow her to elaborate. ‘Billy lives a street over.’ He gestured to the other gravedigger who was returning from the toolshed, where he had replaced the shovels. ‘He can walk you, if you need an escort. Billy’s a good lad.’

Margaret found herself nearly speechless by this kind offer, and stammered her thanks.

She looked towards Billy.

The boy could not have been more than fourteen, lanky but small with malnutrition. His face was black with dirt, but his blue eyes were bright and earnest.

‘Me mam and me live just over from Red Lion,’ he said cheerfully, seemingly oblivious that she was a new widow, abandoned by her family in a churchyard miles from the area of London she used to call home. ‘Not seen you abouts. You new t’ Suverk?’ He laughed to himself.

Margaret was startled by his pronunciation and lost his meaning entirely.

Billy laughed again, showing a mouth of broken teeth. ‘O’ course you are … just follow me.’

The Widow of Red Lion Row by Viveka Portman will be available from the 4th of January 2021

Brothers of the Vine

Brothers of the Vine Forever Evermore

Forever Evermore Women of W.A.R.

Women of W.A.R.