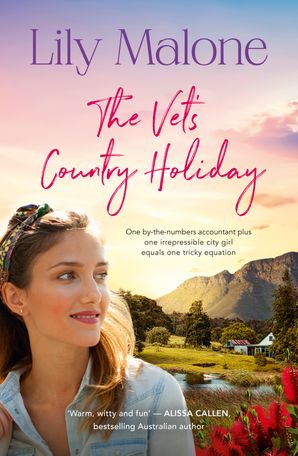

One irrepressible city girl plus a by-the-numbers accountant = a tricky equation…

For city vet Isabella Passmore, the opportunity to pet-sit in the country knocks at the perfect time. Bring on that fresh air! But after three days of holiday bliss, Izzy is bored silly. If the air gets any cleaner, she’ll start slinging mud. Then she gets offered work in the second-hand shop. Saved!

Maybe.

It’s been years since Elliot Field’s parents rolled out the red carpet, but Elliot only needs one day to learn that this welcome mat comes with strings. His parents’ new business is sinking, and they expect him to fix their financial problems.

To prepare for the week from hell, he’ll need a mug that’s not steeped in bad memories, but nothing could prepare him for the employee he encounters at the second-hand shop.

For Izzy, pursuing Elliot is a most welcome diversion from walking another lap of town with the dog. For Elliot, their random encounters add up to the sum of much bigger things.

He’s always been a numbers man and he’s kept his heart locked away, but in irrepressible Izzy, is Elliot’s number finally up?

Come to Chalk Hill for a holiday, they said.

It’ll be fun, they said.

‘Bloody liars,’ Isabella Passmore grumped to herself as the magpies outside her window heralded the start of another glorious Chalk Hill spring day.

She pushed herself out of the comfy warm bed and found a pair of clean knickers before pulling on all of yesterday’s clothes. She was always a big fan of layering, but adding and deleting those layers to match the Chalk Hill weather at this time of year almost required another uni degree.

She grabbed her glasses off the bureau and shoved them on her face, bringing herself into sharp focus in the bevelled wood mirror. Lovely. Her hair looked like she felt: lanky, dull, with no prospect of thrills on the horizon. She pulled a brush through it, then bunched it at the back of her neck and tied it there. Nobody cared what her hair looked like. Tonight she’d give it a wash, but for now coffee and toast were more important and, with that thought, Izzy marched from the bedroom.

‘Right, Bruno,’ she announced to the kelpie-staffy cross lying in his basket in front of last night’s fire, now gone out. ‘What will we do today?’

Bruno slapped his tail against his basket in response and Izzy dragged the toaster out of its cupboard and set it on the kitchen bench.

‘A walk, you say? Wow. How exciting. Where shall we go?’

Bruno bashed his tail harder and Izzy poked the switch to turn on the coffee machine and took the soy milk out of the fridge.

‘The main street? Again? Can you handle the excitement, puppy dog?’

Bruno put his snout in the air and staffy-growled agreement that indeed he could, stretched his front legs out of his basket and arched his back.

Izzy dug in the freezer for the bread and came up to see the black dog watching her every move, tail wagging like a flag in a hurricane. Her heart softened. ‘You’re a good boy, Bruno. Don’t listen to my grizzling.’

She shouldn’t be surprised that Bruno had turned into a great little dog. Her friend Taylor never did anything by halves. Bruno would have been through the best puppy school Perth had to offer after Taylor picked him out from the handful of rescue dogs at the back of Izzy’s small Perth-based animal vet clinic a few years ago. Izzy could mark Bruno down in the ‘positive’ column in terms of the dogs she’d managed to successfully rehome and save. She wished there were more stories like Bruno’s. She wished there were more responsible pet owners like Taylor.

Bruno stretched the only part of him that hadn’t yet left the basket, shook himself, then headed for the dog door off the laundry. It flapped shut with a bang and then, a few seconds later, she watched him through the glass screen doors as he tore a righteous path down the rear garden to chase off the trio of carolling magpies that had now moved from outside Izzy’s bedroom window to the back fence.

Steam shimmered as the fence warmed in the morning sun, drifting above the curved iron capping. It looked like smoke.

She glanced at the clock.

‘Well done, Isabella. That’s a new record!’ she congratulated herself out loud. ‘Eight thirty before you thought about a cigarette.’

She busied herself with the coffee machine and the toast, making a game of getting her coffee made before the toaster popped, and she crunched the toast down with one eye on her phone and the morning’s headlines and thought about what to do with the day to fill the hours.

When Taylor asked her to house-sit in Chalk Hill while she and Abe visited Abe’s biological father in Brugge—their first chance at international travel since Covid-19 changed the world—Izzy had been thrilled. A month of doing nothing except walking the dog had sounded like pure bliss, and Taylor had emphasised the number of hunky country farmer types living in the town …

The first day or two were kind of blissful. The first morning it had been quite lovely to be woken to carolling magpies at the crack of dawn instead of the rattle and bang of the morning garbage truck doing its rounds of Como. Even the second morning when the neighbour’s rooster got in on the dawn chorus it had been nice enough to be woken from a lovely deep sleep by nature. Quaint even.

By day three, it had to be said, the whole wake in the morning with birdsong thing had started to sound a bit tired. Heck, talk about tired, so was she. She spent all her working days surrounded by animals that barked, meowed, tweeted or clucked, and that meant holidays should equal late nights with a book and morning sleep-ins with silence till a decent hour. Like 10 am.

Yesterday she’d decided it was time to fight back against nature. She’d bought a stack of shiny CDs at the second-hand shop in town and tied them into the bushes outside her window. They’d had a plastic snake in the kids’ toy section so she bought that for another dollar and laid it on the outside window sill. Judging by this morning’s skylarking, she figured the magpies were dancing with their reflections in her shiny compact discs and the kookaburras had eaten that menacing toy snake for breakfast.

Sigh. Only four more weeks.

Dear God of Boredom, how would she manage?

Bruno appeared at the glass doors, tail wagging, black nose snuffling the occasional pollen-induced sneeze. Izzy finished her coffee, washed the cup, tried to gauge from the sunlight in the backyard just how warm it would be outside and decided not very.

She futzed around the house (there was no other word for it), put on a load of washing, watered Taylor’s indoor plants, checked for messages from the locum at the vet clinic (none), checked for any Facebook messages (none), did another lap between the fridge, the bathroom and her bedroom and came back to find Bruno in the exact same place, making more of the snuffy nose circles on the same patch of glass and thought, sod it, where are my shoes?

When she started lacing on her walking shoes, Bruno leaped and hopped about the bricks that separated the house from the lawn, turning circles and whining with excitement. How she wished she could summon a tenth of the enthusiasm the dog had for a daily walk.

‘Come on then, boy.’ She took the leash from its hook on the wall and the dog hopped another four circles, did the canine equivalent of a pilot’s loop the loop, and galloped around to the laundry door where Izzy met him and clipped on the leash.

She took them through the gate and closed it behind her and set off for the walk from Taylor’s place on Lavender Lane into town. She told herself to look on the bright side. Maybe there’d be one of those broad-shouldered hunky farmer country types loitering over his morning smoko.

Argh! Don’t think about smoko!

She crossed the dew-drenched lawn, passing the front steps of the house, and when Bruno detoured to sniff at the pot plant by the verandah post, she almost stepped in a small pile of dog poop on the grass. Way too small for Bruno and besides, he’d been securely housed in the backyard.

‘Just about sums up the day so far, Bruno,’ she said, nose wrinkling—her phantom pooper could use more fibre in its diet—and stepped out briskly through the front gate and onto the footpath. There was a plastic bag tied onto Bruno’s leash but she didn’t want to walk with a bag of poop this early in the walk proceedings so she’d scoop the poop on the way back.

The street was quiet except for birds flitting through bushes and the occasional rumble of an unseen vehicle travelling through town. In the patches of shade thrown by the streetscape trees it was cold enough to make her clutch her cardigan across her front and bury her hands in the pockets. When she came out from beneath the trees, the sun warmed her through all the layers, and by the time she got to the main street, long legs a-pumping, she’d peeled the cardigan off and tied it around her waist.

There wasn’t a lot happening along the main drag. There were cars in front of the bakery, pulling in and out. There were people at the post office going about their day and a little girl on a pink bike, too young for school, being pushed along by her mum.

She passed an old man smoking on his verandah who may have been a hunky farmer type last century. He nodded at her as he puffed and she looked away quickly and felt the pang. A woman about her own age walked a dalmatian on a leash. Izzy eyed it suspiciously for a moment, but the dog was too big to be the perpetrator of the poop on her porch.

And that was about it.

That was the sum of the south side of Chalk Hill main street and it was only 10.02 am.

Izzy and Bruno crossed the road and began walking back the same way they’d come. The sun had climbed higher and she peeled off the long-sleeved shirt she’d worn beneath the cardigan and hung it over her shoulders. Grumpy or not, she had to admit the sun felt lovely on her skin.

She passed the liquor store and the petrol bowser, coming up to the butcher and the general store, and she stopped at the second-hand shop and thought about going in. Again. She’d been in that shop every day. Taylor had told the volunteer ladies working there that she had a friend coming to stay and when they’d seen her with Bruno they’d known who she was straight away.

They were lovely old dears, good at chatting. And it wasn’t as if Izzy had anywhere else pressing that she had to be. She’d just make a quick check in case something new had come in since yesterday.

She tied Bruno to a post by a water tap where he would be out of the way and she had her hand on the door to push it open when a red-headed woman burst out with a mug in one hand and something else in the other.

‘Oh!’ the woman said, holding her mug out to the side so the hot liquid didn’t slop and scald them both. There was half a scone in the other hand, piled high with cream. ‘They should move that silly open sign from the middle of the door. You can’t see a thing through it. I didn’t see you! I asked the secretary to minute about the sign at the last committee meeting but do you think anything’s been done? Are you okay? I’m so sorry.’

‘I’m fine,’ Izzy reassured her. ‘You missed me. What about you? I thought I’d tripped you.’

‘You could sue you know. I told them we could be sued. This day and age, you can’t be too careful. A lawsuit’s the last thing we need.’

‘I won’t sue,’ Izzy said, eyeing the quivering tea and the scone-bottomed spiral of cream in the woman’s other hand. OMG that’s a lot of cream.

‘Well, we’re lucky you’re not a lawyer. Give me two shakes and I’ll be right with you. Come in! I have to catch Jenny Dart. There’s a collar in the last bag.’ She took two steps, lifted her chin, the tea and the scone, as if doing that would help project her voice, and hollered across the road. ‘Jen? Jen Dart! Jenny!’

Every person outside the post office on the opposite side of the street (well, there were only two people) turned to see who was yelling, and the red-headed woman started to wave. It was the type of wave that rocked her body, the tea and the scone. There was a lot of teapot short and stout going on. Atop it all, the cream wobbled like Marge Simpson’s hair.

‘A collar came in, Jen!’ the woman shouted.

‘Oh, good-oh, Irene. Can you bring it over? Tipsy’s in the car. I’ll try it on.’

Irene huffed out the side of her lips. ‘That’d be right. She won’t bring the dog here. I have to go over there. Well, it’s all for a good cause, Irene Loveday. Have to remember that.’ She hollered across the road, ‘I’ll be two shakes.’

She turned back into the shop. The door whumped closed with a sprightly tinkle of a bell and Izzy felt like she’d witnessed a tsunami or an earthquake, or both. Her head spun.

People didn’t come in or out of her vet clinic like tsunamis. Some of the dogs did. There were dogs that loved visiting her for check-ups and jumped all over the staff and couldn’t wait to leap up on the examination table, and there were dogs who’d come in, tail between their legs, already familiar with veterinary sights and smells and nervous about what they were here for this time. Usually the males.

Generally though, people came in gently, leading or carrying an injured animal or hefting a bird or cat cage, constantly on the lookout for other dogs or other cats. No pet owners came in holding a cream-loaded scone lest every labrador in the waiting room jump on them and it.

The door opened again and Irene poked her nose out. ‘Come on in, love, don’t be shy. You’re Taylor’s friend, aren’t you? I recognise Bruno. You can keep an eye on things in the shop while I show Jen the collar. You won’t mind doing that for me?’

‘Um—’ Well … what else did she have to do this morning? Nothing. And who was afraid of a little tsunami anyway? Izzy had practically wished for the excitement of a tsunami just a few hours ago.

‘Okay. Sure.’

Elliot Fields drove into Chalk Hill for the first time in six years and was thinking that nothing had changed until the new tourist attraction sign for waterskiing leaped out at him and he thought maybe a few things had changed after all. He slowed and indicated to turn into Chalk Hill Bridge Road.

A much larger sign was printed on the old shed that had propped up the corner of the highway and the bridge road for half a century. It showed two kids on skis being towed across a large expanse of pristine blue water behind a powerful boat that left a bow-wave of white.

Waterski Adventure Playground, declared the sign. Cake. Coffee. BBQ facilities. Family Fun. 9 km.

A big white arrow pointed south-east.

How much had his father paid the graphic designer who came up with the billboard? Maybe the marketing expense was the reason the ski park wasn’t making money. If his father had agreed to email him the financial statements, Elliot would have known then and there. But Elliot’s dad, Dylan Fields, dubbed Pickles long ago by the entire town, had been adamant Elliot needed to visit the farm for himself and get a handle on what was going on, not just look at it over the computer … so here Elliot was—thirty-two years old and still he sucked at saying no to his folks.

Chalk Hill Bridge Road had always been bitumen as far as the bridge before it turned to gravel, but now it had been widened and the bitumen continued on. A single white line cut it in two and the old bridge had new timbers and a coat of fresh white paint. Two cars could cross it at the same time, not like the old days where someone always had to wait if they met another car coming in or out of town.

Elliot’s gaze swung left and right. The Nillsons’ old place had been flattened. It was now a row of holiday units with a gated swimming pool at the front. Next door to that was a new café where Irma Honeychurch’s cottage had once stood.

Hang on. Elliot slowed as he drove past. Still stood. He recognised the traditional old porch at the front and at the back the bright green tips of the mulberry tree stretched up over the shining restored iron roof. He remembered pink fingers and stained clothes from mulberry fights with the Honeychurch kids, and the day Dan moved the ladder and Jake Honeychurch fell out of the tree.

His heart shrank a little in his chest. No matter how much he should be immune by now, memories of his big brother had a way of gutting him whenever they snuck through.

Elliot accelerated across the bridge, listening to the tyres rumble. He picked up speed.

A tingle prickled the back of his neck as he passed old landmarks and left the town behind: the dead tree that got struck by lightning in the storm of 2006; the hayshed which was rebuilt after the owner’s kid burned it down in 2012. The kid told everybody the hay self-combusted. They believed him too, till years later he confessed to lighting a match in the dry weeds at the back of the shed just to see what would happen.

The first sign sat boldly in the paddock at the corner boundary of his parents’ farm—an identical billboard to the one painted on the Hendricks’ shed back in town—and then there were smaller triangular A-frame posterboards spaced about two hundred metres apart along the road verge on the right-hand side. These said: Waterskiing, Café, Coffee & Cake and Playground respectively and they counted down the metres each time. 800 m, 600 m, 400 m, 200 m.

He slowed, turned off the bitumen onto the gravel and stopped, squarely between two open intricately carved wrought-iron gates.

The dam was enormous. Enormous didn’t really do it justice. It looked like his dad had picked up one of America’s great lakes and plonked it nine kilometres south-east of Chalk Hill town. It shone like a glassy mirror under the morning’s expanse of blue sky, a silvery-grey, the colour of cold steel.

The two jetties jutting into it were new, as were the timber landings spaced on the carpark-side of the lake. Two powerful-looking speed boats were moored either side of the larger jetty. He counted three aerial ski ramps zig-zagging across the water’s surface, sticking up like shark fins.

Green grass mounds and healthy swathes of landscaping plants, some still shrouded in protective plastic skirt coverings, dotted the earth that had been piled around the dam’s circumference and there were tables and bench seats all around, and a slew of small gazebos covering what must be gas barbecues.

No expense spared, his dad had said.

Elliot let out a whistle. ‘You’re telling me.’ It must have cost a bomb. Where had his parents got the money to do all this?

After another half a minute, he eased his foot off the brake and followed the sweeping driveway around the corner of the dam and along the left side of a two-way entry that wrapped about a showy fountain and a garden bed of fancy grasses and washed river stones.

He tried not to gawp at the park office and the café, where outdoor chairs had been pushed beneath tables overnight and tilted with their shiny backs up, tipped like old men fallen into their cups. He checked his watch. The park opened at 10 am. It was too early yet for customers, and possibly too early for staff, although there was one car in the designated staff parking area behind the café, a silver Toyota four-wheel drive.

Elliot continued past the café. The sign to the left said private, and he drove that way. The other sign pointed to customer parking, BBQs and skiing. When he looped to his left he could just make out the bright blue flag of a shade sail over a mess of slides and climbing towers, and the shining steel of the top of what might have been the flying fox.

With each turn of the tyres, the lump in his throat grew.

There were the two gate posts with red-flowering bottlebrush trees either side, and the hedge grown so thick he couldn’t see the fence, let alone his parents’ house, till he was all the way through and the jungle opened up.

He and Dan used to climb in that hedge. There was a time it stretched all around the house, but he could see a gap on the northern side now, a view knocked out of the hedge’s green wall like a missing front tooth.

Elliot rolled to a stop before his childhood home.

The things that could grow and move on in the six years since Dan’s funeral were all bigger, greener, bushier. The things that couldn’t grow were the same, like the access ramp sliding along the front with its steel handrail and the steps that were used less and less and now looked like they’d been put there to be a stepladder for his mum’s geraniums and maidenhair ferns.

Then his mum was there at the top of the ramp, half-in-half-out of the shade of the verandah, smiling at him and waving for all she was worth. And for a second there, all Elliot wanted to do was cry.

On sale 30th March 2022

Brothers of the Vine

Brothers of the Vine Forever Evermore

Forever Evermore Women of W.A.R.

Women of W.A.R.