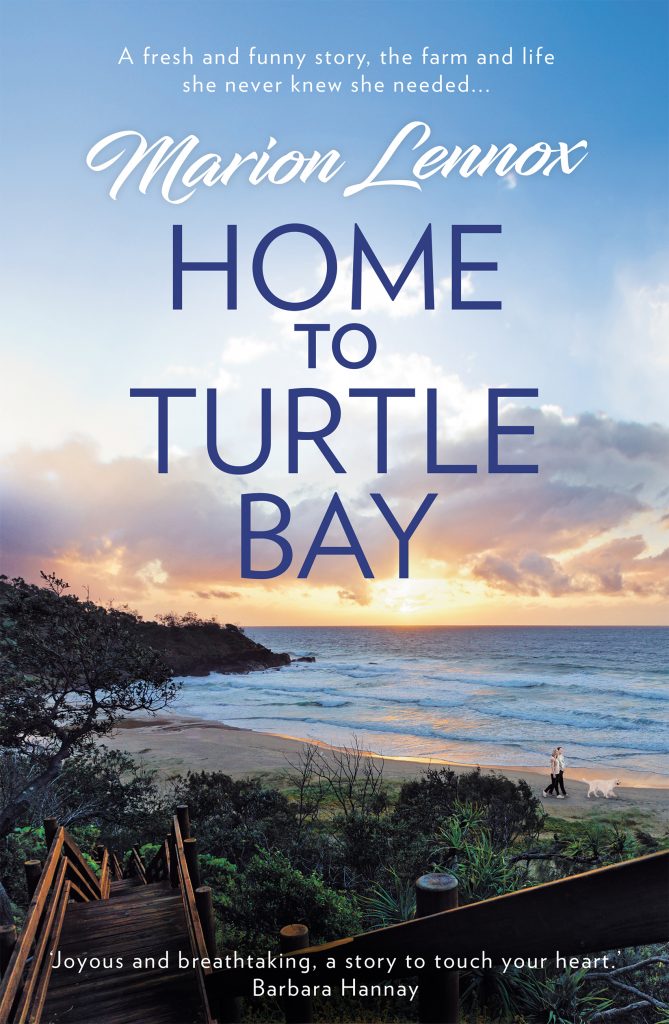

A warm and witty multi-generational romantic comedy, set in a coastal Australian farming community, from international bestselling romance author Marion Lennox.

A warm and witty multi-generational romantic comedy, set in a coastal Australian farming community, from international bestselling romance author Marion Lennox.

Dr Jennifer Kelly has reached the pinnacle of her career as a successful Manhattan obstetrician, complete with ambitious, blue–blooded fiancé. After a desolate childhood with a distant grandmother, life seems everything she’s ever wanted.

When a grandfather she’s never heard of leaves her a dairy farm on an isolated Australian island – plus one depressed dog, thirty geriatric cows and a bunch of ancient surfboards – she plans a quick trip to put the farm up for sale. Her aloof, socialite grandmother Muriel is appalled, yet insists on accompanying her.

Once there, Jenny finds herself caught, by cows, by turtles – and by Jack McLachlan, the overworked island doctor who desperately needs her help. Muriel’s caught too, with ghosts of her wartime past threatening to crack the shell she’s built with such dedication and care.

But isn’t Manhattan their home? How can two women give up the perfect world they’ve worked so hard for by taking a chance on…life?

‘Joyous and breathtaking, a story to touch your heart, make you smile and see the world as a better place.’ – Barbara Hannay

1

acid drop n. the bottom of the wave collapses; there’s nothing to do but fall.

‘I don’t care if he’s left you a dozen surfing schools. You’re not leaving Manhattan—but you do need to deal with this dog.’

My grandmother … Uh-oh.

Isabella Clayburgh—the Isabella Clayburgh—was on my examination couch, naked from the waist down. I’d been listening to her baby’s heartbeat. It was a nice, strong heartbeat. Now that my grandmother was in my consulting room, the baby’s beat was about quarter the rate of mine.

Heartbeat aside, I needed to act professionally, as if a grandmother and a dog bursting into an obstetrician’s consulting room didn’t fuss me at all. Flipping Isabella’s gown to near decency, I shielded her as much as I could, which, considering the stage of her pregnancy, wasn’t shielded enough.

‘Grandma, can we talk outside? And what’s the dog—’

‘Don’t call me Grandma. This man … Leaving you his farm … Calling it a surf school. Sending you a dog—a dog—all the way from Nautilus Island. And calling himself your grandfather! You don’t have a grandfather. Have I ever said you have a grandfather?’

‘No, but …’

‘There you go. You don’t!’

Muriel, in case you’ve missed it, is insane. Gorgeous, but nuts.

‘But everyone has a grandpa.’ Isabella’s sculpted blonde head was poking out from behind me, apparently unconcerned by her lack of clothes. ‘Hi, Mrs Kelly.’ She checked out the shaggy, off-white mutt at Muriel’s side. ‘Cute dog.’

It wasn’t cute, I thought wildly. It … she … was huge.

‘It’s not my dog,’ Muriel told her. ‘And Jennifer doesn’t have a grandfather. She has no father. She has nothing but what I’ve given her.’

Mistake. Isabella might be an airhead, but she does have a basic grasp of family trees. ‘She must have,’ she reasoned. ‘Unless she’s a test-tube baby. Did they have IVF back then?’ Her wide blue eyes turned to me, inspecting me like I was some sort of test-tube bug.

Muriel glared, as if Isabella was the bug. Then she reverted to her fury.

‘For fifty years I hear nothing, and now he’s sent his dog. And his will says he’s left you a surf school. And a boarding house! Of all the nonsense …’

‘A surf school? On Nautilus Island? You mean the Nautilus Island, off Australia?’ Isabella hauled herself into a sitting position, smoothing her gown tenderly over her eight-month bump. It was the first tender thing I’d seen her do for her unborn child. ‘Jenny, this is awesome!’

Grandma turned her glare back on Isabella, and Isabella—Isabella Clayburgh—closed her mouth.

Muriel Kelly, my seventy-five-year-old grandma (not that I’m permitted to call her that) is something of a force to be reckoned with here in Manhattan. She’s the product of English aristocracy and American money, and she’s considered a style icon. Everything she does is noted and copied, but all I’ve ever been able to find out about her as a young woman is that she made an unfortunate match somewhere far from Fifth Avenue. She says it was nothing to do with me, and I have no right to know the details.

But that match can’t be entirely forgotten, for there’d been a baby: my mother, Sonia. Even what I know about Sonia is sketchy. I remember snatches of our lives together, wandering from camp to camp with various gentle backpackers in Nepal. She had the same frizzy red hair as I do—I remember her trying to comb it, laughing, telling me I’d hate it all my life. Which I do. I remember long skirts and patchouli oil and singing. I remember making tea once, a lot of people helping and laughing, and that it took the best part of an afternoon. I remember she was often ill and so waif-thin that her big shiny jewellery cast her face in the shade.

I remember appalling loneliness when she was ill and I didn’t know how to help her.

Sonia died when I was seven and I still don’t know why. Drugs, I guess, or maybe she was sick and the local hospitals couldn’t help. Or maybe she didn’t ask for help.

Sometime after her death, someone plucked me off the streets of Nepal. I have a vague memory of a man with a scarred face feeding me fish soup, and the same man shouting at people around me, but that’s a tiny scene in a vast patchwork that’s never been sewn together. I remember a hospital and a woman in an orange jacket with a clipboard. I remember questions and a lady washing me and dressing me in new clothes. Finally there’d been a long plane flight to meet Muriel. I’d lived with my grandmother since then, but with nannies, huge houses and my grandmother’s social butterfly existence, I’d never seen much of her.

I surely wished I wasn’t seeing her now.

‘Isabella, would you excuse us?’ I was trying to steer Muriel and the dog out the door but Muriel wasn’t the type to be steered.

‘I’m staying put until you promise you won’t go.’ She was holding the dog’s collar with one gloved hand and with the other she pointed an imperious finger at Isabella. ‘You go.’

‘I’m not going anywhere.’ The normally bored beauty was quivering with interest. ‘A surf school on Nautilus Island? It’s supposed to be fabulous. Subtropical island, surfers, cabana boys, nothing to do but drink and tan … Ooh, Jenny, this is so cool!’

‘Jennifer’s an obstetrician,’ Muriel snapped.

‘I am. And, Grandma, I’m consulting. Privately.’

‘I can see that. I’m not stupid. Who is this?’

‘Me?’ Isabella demanded, dumbfounded. ‘You know who I am. Everybody knows who I am.’

Oh, God. Two society beauties … and no room for me in between.

My grandmother is tiny, about four feet eight inches in her stockinged feet, with a beauty that’ll stay with her until the end. She was wearing a dove-grey dress straight off the Paris catwalks. She’d teamed it with elegant, wrist-length gloves and an antique silver necklet that should be locked in a bank vault. A wispy, feathery fascinator nestling on her bobbed, blonde hair completed the picture of a woman who’d cared about beauty all her life. For a woman of seventy-five, Muriel looked fantastic.

Isabella also looked amazing. As always. Her beauty is her fortune, and she works at it every waking minute. She has youth and bubbly good humour, and she surely has confidence, but right then Muriel had the advantage. Isabella was wearing nothing but a medical gown (designer fabric—we are exclusive—but medical gowns are medical gowns) and she was almost eight months pregnant. Isabella was, however, my most important client. I needed to keep my job. I had to do something. Fast.

‘Muriel, please.’ I threw an anguished look out to Nora, but my usually competent receptionist simply held up her hands in surrender.

‘Ask this woman to leave,’ Muriel demanded. ‘We have business to discuss.’

Isabella shook her head. ‘Uh-uh, Mrs Kelly. This is my appointment.’

But then Muriel’s eyes narrowed. ‘Isabella Clayburgh. You’re the idiot who married Lionel Clayburgh the … what is it? Sixth?’ Recognition and contempt were mixed to perfection. ‘Pregnant already. You fool.’

‘Grandma …’

But Muriel, mid-tirade, was unstoppable. ‘Your husband’s family hasn’t made a marriage last for two hundred years. The Clayburgh talent is hiding assets in divorce settlements. The skill’s embedded in the family genes, and they hone it. That bottom-feeder Lionel will use you as an incubator. Get yourself a good divorce lawyer, fast.’

And then Muriel’s face crumpled. Tears rushed down her carefully made-up face, and her legs seemed to give way under her.

Muriel crying? I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

I made a frantic gesture to Nora, who approached with caution—she told me later Muriel had swiped her with her purse to get past her. We half led, half carried the weeping Muriel into my second consulting room. The dog plodded despondently beside her, head low, like a dog about to face a firing squad.

If I was stuck with an angry Muriel, I might feel the same.

We pressed Muriel into an armchair. I put a hand on her shoulder in what I thought was a gesture of comfort and she attacked me with the purse. Obviously the old Muriel was still inside.

‘Grandma, can you tell me what’s happening?’

‘Leave me alone.’

Finally, an order I was happy to comply with.

‘Keep an eye on Mrs Kelly,’ I told Nora in my best Doctor Voice. ‘When she stops crying, tell her I’ll be back as soon as I can. Offer her coffee and the new Vogue.’ I eyed the dog with unease. Muriel had never had a dog in her life, and I surely hadn’t been permitted to keep one. ‘Maybe some water for the dog? But Nora, if you let her in with Isabella again, there’ll be vacancy ads on the internet by tomorrow. For both of us.’

‘Don’t leave me,’ Nora said—frantically—but I was already gone.

Deep breath. Back to Isabella.

Isabella was calmly pulling on her clothes. She seemed a lot more cheerful now than when she’d arrived, much more cheerful than you’d think gossip and insults could make her.

‘Sorry about that.’ I closed the door, leaning against it for support.

Thankfully she seemed to have skipped over the insults. ‘Jenny, do you really have a surfing school? On Nautilus?’ Her eyes were enormous.

‘Heaven knows. To be honest I think my grandmother’s certifiable. But we need to talk about your baby.’

‘Must we?’

‘Isabella, you’re well into your third trimester. You have no choice.’

‘Fine.’ Now she was glowering, clearly upset that I wouldn’t play her game. She’d been trying to distract herself from this pregnancy since conception, and she didn’t like me pinning her down. ‘You swear you’ll be here when I finally deliver?’

I took a couple of deep breaths and returned to my desk. Given the Clayburgh profile, this question was a no-brainer. ‘Of course.’

Isabella checked her eyeliner. How a gynaecological examination could have messed with her eye makeup wasn’t clear, but no one hurries a Clayburgh. No one—excepting Muriel, it seems—even interrupts a Clayburgh.

At least Isabella was ready to admit that this baby was a reality. It was an improvement, but we needed to take it further. I glanced warily at the door, but whatever Nora was doing seemed to be working, so I relaxed a bit and went back to my normal wait-for-patients activity. Which is sketching doodlebugs.

A surfing school? My surfing school?

A surfboard appeared under my doodlebug, and the beginnings of a very small wave.

Forget Muriel. Forget surfing schools. Concentrate on the Clayburgh. Isabella gazed a moment longer into the mirror—checking the perfection of her cupid’s bow lips. She then seated herself gracefully in front of my desk. I pushed my doodlebug sideways into the trash. Surf on, tiny bug. I wished I could do the same.

‘Okay. So I saw a thing about this on television last night,’ she said, waving a manicured hand in the general direction of her bump. ‘Apparently you can make it happen any time after thirty-six weeks. I’ll have less chance of stretch marks, and everything can go back to normal.’

Normal? Coping with a newborn?

But then, nannies would already be installed in the Clayburgh nursery. Personal trainers would be limbering up for the post-natal workout. Birth meant Isabella could get back to her career of being beautiful, which meant I had a job and a half to persuade her to keep this baby on board.

But I could do that. To my grandmother I may be mousy Jennifer, with a dress sense so conservative that without the red hair she swears I could be taken for Nancy Reagan, but as obstetrician to some of New York’s wealthiest women, this discussion was what I did best. I leave the hysterics to the pretty ones. I’m a professional.

‘I know you’re uncomfortable, but induction brings with it a lot of unnecessary risks for the baby,’ I told her.

‘Then organise a caesarean,’ Isabella snapped. ‘The book says caesareans don’t hurt, and Lionel says we’re sixty percent less likely to sue if I have one.’

That was something to think about. I didn’t need to search my notes to see what my boss had written—and underscored—the day he’d told me Isabella was to be my client. Isabella’s husband, Lionel, had spent his formative years in law school in preparation for inheriting the family’s billions. There he’d discovered a passion. Lionel didn’t take legal action against doctors for money. He did it for fun.

No matter. One of the reasons I’d achieved a place in this prestigious birthing unit—and the major reason Isabella had been steered my way—was that my litigation record was clean. This could even be seen as a challenge. If I could deliver this high-profile baby without drama, my client base would go through the roof.

Maybe Isabella could have a caesarean? A sneaky voice in the back of my head was lining up caesarean indicators and prodding them forward in a tempting conga line. Isabella’s body-fat ratio was low, and that could be used as an indicator …

Okay, no. One of my clients was Isabella’s unborn child, and he’d be a Clayburgh as well. Litigation now, or litigation in thirty years for post-traumatic stress from an unnecessary caesarean?

Maybe not.

‘Isabella, there’s no clinical indication for a caesarean. Your baby’s beautifully normal. You’re looking great. Your pelvis is broad enough to allow …’

‘You mean I’m fat? I know I’m fat. I can’t stop gaining weight.’

I thought of the endless discussions over the past months. ‘Isabella, mango sorbet does not contain calcium, dairy products, or probably even fruit. The fact that it’s bought at an ice-cream bar doesn’t count. Drink a mango smoothie instead. Plus everything else on the nutrition sheet.’

I’d said it over and over, uselessly, but the major development stages were now complete. This baby was on its own.

‘I’m saying you’re carrying a lovely, slim baby,’ I told her. ‘Just like his mother—which means you can look forward to a normal birth. Your baby’s growing, not you, and everything’s as it should be.’

But Isabella, still upset and nervy, showed no sign of calming down. ‘The show I watched said it’ll hurt. Hurt as in agony. It said Queen Victoria used enough chloroform to knock out a horse, and she loved it, but you won’t give that to me, will you? Is that true? Not even if I pay?’

The effect of chloroform on a newborn’s breathing? Maternal heart failure? There was the stuff of nightmares.

‘No. No matter what you pay. Drugs that cause unconsciousness can seriously affect your baby. You don’t want that.’

‘I don’t want it to hurt me. Can’t you make it happen without the pain?’

‘There are things we can give you to help. Isabella, a caesarean would cause you more discomfort after the birth. If you need it we can give you an epidural injection. That’ll block the pain below the waist. Natural birth might stretch your muscles to their limit, but a caesarean forces me to cut. You won’t be able to do your normal exercises for weeks after you give birth, because you’ll need to heal before you start. It’ll take a lot longer to get your body back into shape. Why do that if you don’t need to?’

There was silence while Isabella thought that through. She turned again to the mirror, considering the muscles in question.

Time for another doodlebug? Another little surfer?

Why had this idea—no matter how improbable—of my inheriting something upset Muriel so much? Property, assets, social cache, these were the things Muriel lived by.

And what was with the dog?

Stay focused, I told myself sharply. Boredom must have been extreme last night for the beautiful Isabella to watch a documentary. Actually, considering the rumours flying around town about Lionel, boredom might well be a way of life for her.

Isabella had been tricky as a client, swinging one moment from demanding—almost pleading?—that I be her friend and the next to remembering her status and treating me as the hired help. A beauty queen who’d ‘married up’, famous for, well, being famous, I thought of the circles she moved in and diagnosed bone-deep loneliness. But that wasn’t my problem. She was my job, nothing more.

‘Fine.’ She seemed to be griping directly at her stretched and fatless abdominal muscles, now clearly The Enemies. ‘No caesarean.’ But things clearly weren’t fine. She turned from the mirror and concentrated on me. ‘You will be here?’

Why was she worrying so much? What could go wrong for a Clayburgh?

‘Of course,’ I said again. I’d be at this birth if my bosses had to drag me here in chains. Richard, my fiancé, might even help attach them. This one birth amongst the hundreds of exciting, loving, moving births I attended for a living had every society tabloid agog, and Richard, too, was excited. He had a point—it was the single most important step in my career.

‘If I’m in pain …’

‘I’ll do something about it.’

‘I’m paying for the best. You’re the best.’

‘Thank you.’

‘But you’d better not mess me around.’ Way to break the charm, Isabella, I thought wryly, but she was oblivious. ‘You’re only as good as your last birth. If anything goes wrong, Lionel will sue you to bankruptcy.’

‘That’s his right.’

That brought silence. She chewed her bottom lip for a while and I could see fear working behind her lovely facade. On the surface Isabella had the world at her feet—just as on the surface I’m mostly confident and in control—but who’s to know what goes on under the surface?

I thought of Muriel’s extraordinary outburst. I’d never seen her surface crack; not once since I was seven. I didn’t think it could.

‘Lionel doesn’t understand,’ Isabella muttered, suddenly almost wistful, and I hauled my attention back to my client.

I’d agree with her there. I’d met her husband. I wish I hadn’t. Isabella must surely be aware of Lionel’s extramarital activities, and Muriel’s appalling assessment of her marriage wouldn’t have helped at all.

Think of a tactful answer, Jenny. Fast.

‘It’s hard for a man to understand pregnancy.’

That meant more silence. Finally, though, Isabella slid her silver-painted toes into shoes that were far too high for a heavily pregnant woman, and rose, reluctantly, to leave.

‘It’s just … I feel so fat,’ she whispered, and her face puckered.

‘You look lovely,’ I told her, even going so far as to pat her on the arm. It’s not the sort of gesture that comes easily to me, but I’ve learned it works. ‘You realise pregnancy’s the latest fashion? Everyone who’s anyone is having a baby. Your friends must be so jealous.’

‘My friends … yeah. I guess I’ll see more of them after the baby’s come. It’s such an effort to …’ She stopped herself. Admitting it took hours to keep herself looking as gorgeous as she did? No. ‘I don’t suppose you’d come with me now to grab a latté?’ she asked. ‘I’m even drinking decaf, just like you told me.’

I could hear desperation behind her words. Another appeal to be her friend? But there was no way I could accept. Even if I wanted to get involved—which I didn’t—there wasn’t time. ‘I’m sorry, Isabella. It sounds like fun, but you can see that I have other women waiting for their own appointments.’

Isabella’s doll-face lost even more of its sparkle. ‘I just wish it was over. If I knew that Lionel would stay with me … ’

I wondered that, too, but it wasn’t my place to say it. ‘I’ll be here, even if he’s not.’

‘You’ll be back from this island?’

‘I’m not going to any island.’

‘But it’s Nautilus. It’s gorgeous.’

‘I don’t know anything about it.’

‘I saw it last year when we went to Sydney for New Year’s Eve. You should have seen the fireworks on the harbour … Awesome. On the way back we stayed at Lord Howe Island so Lionel could dive and we flew over Nautilus on the way.’ Her face lit up again. ‘Do you know where it is?’

‘No, but … ’

‘It’s about three hundred miles off the Australian coast, out from Sydney, higher though so it’s warmer. From the air it looks fabulous. Apparently they have the best surfing in the world, or so Lionel’s partner told us, but there’s nowhere decent to stay. Most of the island is some sort of national park, and he says the locals hardly ever sell. If you’ve inherited land there, you could be a squillionaire.’

‘A surfing school doesn’t sound like land.’

‘But your grandma called it a farm so it’d have to have land. And if it’s a surfing school there’ll be a beach. Do you really not know?’

‘I don’t.’ I opened the door and stood aside to usher her out. She walked out, then stopped and turned back.

‘I don’t know anything about the Kelly your grandma married.’ For this walking who’s-who of Manhattan aristocracy, not knowing was clearly bugging her. ‘Where does your name come from? Kelly? Your grandma’s parents were Fletchers. She’s only been with Al Heinrigger for about two years. Lionel says his family has more money than the Clayburghs. Before that she was with Max Felderhouse. He’s loaded, too, but she wasn’t married to him, either.’

‘Mmm,’ I said flatly, feeling more than a little uncomfortable to be having this discussion in my waiting room.

‘Then who’s Grandpa Kelly?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘Really?’

‘Really.’

‘Ooh.’ Isabella was suddenly a bloodhound on a scent. ‘How cool. A mystery … He must be an islander, and now he’s left you a surfing school.’ She was obviously using this to push her own worries aside, and I didn’t have the heart to stop her. And the situation didn’t hurt me. I was clearly rising in her estimation—an obstetrician with a surfing school on an island her associates lusted after. Awesome, she’d said. A surfing school must be the ultimate designer toy.

‘You so need to see it. But will you have time before I deliver?’ Some fast arithmetic was going on. Her face cleared. ‘If you won’t give me a caesarean then we have over a month. You could get there and back in two weeks. That gives you heaps of time. How will you get there? Will you hire a jet?’

‘I can’t hire a jet.’ Good grief.

‘Of course you can.’ Isabella was off and running. Or off and surfing. ‘I’ll ask Lionel to lend you ours. You won’t let me fly from now on anyway, so we’ll hardly be needing it. Now, you’ll need new swimsuits, and a good tan. Liselle on Fifth is always booked out, but tell her I sent you and she’ll bump someone. You need three coats, but the colour lasts ages. Look.’ She lifted her skin-tight top and exposed her pregnant bulge. For the second time now, she looked almost tender. ‘So smooth.’ She hesitated, thinking hard. ‘Luggage. There’s a new line just come in at …’

I tried not to giggle. ‘Isabella. I can’t just drop everything and go island hopping.’

‘Why not?’ She sounded astonished.

‘I have women booked for births. Three of those ladies are here right now.’ They were, too, and they looked just as interested as Isabella. Damn it, read your glossy magazines. At the look on their faces I tugged her back into my consulting room and pulled the door closed again. I was scared of what Isabella was about to say— and sure enough, she said it.

‘So what? Miss a few births. They’re not important. As long as you’re back for me.’

‘But …’

‘Jenny, a surfing school.’ Isabella was suddenly deadly serious. ‘On Nautilus. I’d even swap Lionel’s grandmother’s diamonds for it. More,’ she added expansively. ‘I’d even swap my shoes.’

‘Your shoes?’

The beauty’s face twisted into a wry smile. We both looked down at our shoes. Shoes were my one indulgence—I loved them, but mine weren’t a patch on Isabella’s. ‘Okay, maybe not my shoes,’ she conceded. ‘But a surfing school … Jenny, you need to go.’

image

I saw my next clients. I may have been a little preoccupied, but they were forgiving. They’d sat in my waiting room for long enough to know that something unusual was going on, and if Isabella seemed fascinated, so were they.

Muriel left without another word to me, but she left a message. ‘Tell my granddaughter that if she goes to Nautilus, I wash my hands of her.’

She left the dog behind. When Nora tried to protest she gave her a look of scorn and left anyway. By the time I’d finished consulting, Nora had sent out for a hamburger. The dog had therefore been fed and was sleeping under her desk.

‘She’s lovely,’ Nora told me. ‘If a little depressed. She ate the hamburger, though. Her name’s Drifter. It says so on her tag.’

‘What sort of name is that for a dog?’ I bent down and stroked her behind her white, shaggy ears. She seemed placid enough but sort of resigned. Worried?

‘You and me both,’ I told her.

‘She looks sad,’ Nora said. ‘Maybe she’s missing your grandma.’

‘She’s not Muriel’s dog.’

‘Then whose? Oh, and a courier’s just delivered a letter from some legal firm. You want it?’

I wanted it. I left her with the dog. I sank into my chair in my nice, safe consulting room and slit it open.

It seemed I had indeed inherited a farm. Two hundred acres on Nautilus Island, one farmhouse (including contents) at a place called Turtle Bay, and one boarding house in the island’s commercial centre. The letter said the boarding house was set up as a hostel. It’d been recently renovated but strangely it had been unused for thirty years and was unused now. I also received the title to one registered surfing school.

And one large dog.

The concept was surreal.

I rose and pressed my nose against the window, staring across the grey Manhattan cityscape for a long time. Finally I told Nora she could go home, then rang Richard.

Thirty minutes later Richard breezed in. He looked crisp, expensive, controlled—a surgeon at the top of his game. He’d obviously moved fast—or his secretary had. He was already carrying printouts of an internet search on Nautilus Island, and I’d never seen him look so excited.

‘Honey, this is fantastic! A legacy on Nautilus … I’ve done a fast read. It’s north of Sydney but a long way out, Australian territory but only just. There’s a dairy community that exports specialty cheese. I guess that’s where your farm comes in. There’s a tiny town, imaginatively called The Cove, but not much industry. The locals seem mostly to be the descendants of an early shipwreck. The survivors were Scottish which explains why a dairy industry started in such a place. Oh, and it’s famous for its surf.’

‘Which explains the surfing school.’

‘I’d imagine, yes. There’s a tiny hospital providing basic needs but locals fly to Sydney for anything major. There’s a seaplane service or helicopter evacuation for medical emergencies. No airport. It has a school and a couple of churches and shops. There’s also some sort of boarding house—that must be what the lawyers are talking about—but it seems to have been closed forever so there’s no tourist accommodation. Surfing fanatics hitch to the island on fishing boats, but they need to either beg a bed from the locals or pitch a tent. But here’s the best part. A yachting resort’s mooted for construction—somewhere to moor between Sydney and New Caledonia. None of the neighbouring islands have a safe harbour. Developers are sniffing the place in anticipation, but the island is mountainous and there isn’t a lot of flat beachfront to go around. Apparently the locals hold for generations and won’t sell, but it seems the land you’ve been left is on Turtle Bay, one of the few flat spots on the island. So there you are, honey. It could be a fortune for the taking.’

Finally I got a word in. ‘Richard, there’s a dog.’

He’d been too preoccupied with his maps and his facts to notice, but Drifter was limp under my desk. Her body language was getting more and more desolate—everyone’s deserted me and I don’t belong here. Richard stared down at her and she stared back, her brown eyes limpid pools of misery.

‘What the …’

‘She’s part of the package,’ I told him. ‘She’s my grandfather’s dog. She was delivered to Muriel who brought her straight to me.’

‘You can’t keep a dog.’

‘No.’

‘Take her to a shelter.’

‘I can’t do that.’ I’d been staring into those depressed eyes for too long.

‘Of course you can. Make a donation.’

‘Richard! She’s my grandfather’s.’

‘And he’s dead. I didn’t even know you had a grandfather.’

‘Everyone has a grandfather.’ I was parroting Isabella.

‘You know what I mean. Okay, you had a grandfather and now you know who he was, but he’s dead. You don’t owe him anything and you don’t want his dog.’

‘She must have been flown all the way from Nautilus.’

‘Send her straight back.’ He frowned. ‘Quarantine might be an issue but if she’s only just arrived … We need to get her back to the airport holding facility fast. Then all that’s left is for you to get to the island and back before the Clayburgh baby arrives.’

‘I can’t go!’ To say I was astounded was an understatement.

‘Of course you can, sweetheart.’ He kissed me briefly, a man in a hurry. ‘You’d be crazy not to. This could be the opportunity of a lifetime. It may make us a fortune. Alleviate your conscience and take the dog with you. Find someone to care for it when you get there—pay if you must. Then check out the island, figure the value of this place and put it on the market. It shouldn’t take you more than a week. I’ll put my secretary onto organising flights—for you, and for the dog.’

‘You can’t come with me?’

‘Have you forgotten the conference?’ He sounded shocked. ‘Sweetheart, I’m the keynote speaker.’

‘I … no.’ Only I had. I’d forgotten everything.

I had a grandfather—or I’d had one.

I had a surfing school on the other side of the world at a place called Turtle Bay.

image

Richard closed the door behind him. I was left with the letter, the dog and a growing certainty.

He was right. To sell without seeing—and risk being conned out of a fortune—did seem naive. And maybe I could learn something about a grandfather I’d never met.

I knew three facts about my family. One, I’d been born in Nepal. Two, my mother was called Sonia and three, my grandmother was Muriel. I wouldn’t mind knowing a bit more. I couldn’t keep the dog, and dumping it in a shelter in New York seemed heartless. And Muriel had been so adamant about me not going that I thought, Damn it, I am going! Me and Drifter.

A guy in uniform arrived, sent by Richard.

‘I’ll take the dog, ma’am,’ he told me. ‘She’s being returned to Nautilus?’

‘I … yes.’

‘We’ll take care of her from now on, then,’ he said and he left, tugging Drifter behind him.

She looked back at me once, and the reproach in her eyes almost did me in.

‘You’re going home,’ I told her but the door had already closed behind them.

She was gone, and I was going after her.

2

bump n. a long, low swell, far out; a warning of what’s to come.

Four days later, fake tan still sticky—for future reference, three coats is overkill—and with a new bikini that cost more per square inch of fabric than any item of clothing I’d ever owned, I was in the sky, heading for Nautilus Island.

I didn’t accept Isabella’s offer of the jet. ‘Too risky,’ Richard decreed. ‘Blurring professional boundaries is asking for trouble. Besides, there’s no runway.’

But I did accept Isabella’s advice on almost everything else.

And it was exciting. I have the pale skin that goes with being a redhead, but now I was tanned. I’d done a fast spend on new clothes, conservative but classy, and all the way to the island I savoured the prospect of me, Dr Jennifer Kelly, proprietor of an island surfing school, sunning myself on golden beaches in between negotiating the sale of my prestigious coastal property.

I’d negotiated—with difficulty—two weeks’ leave. Richard was in the middle of his conference. ‘You’ll be fine alone,’ he’d said, but I wasn’t alone. Drifter had been kept in quarantine until I left. She was now in the back of the plane.

And then there was Muriel.

I’d thought Muriel would have a stroke on the spot when I called from my office to say I was going. She was almost apoplectic. But late that night her return phone call woke me. ‘You’re a fool. You can’t let well enough alone. Why do you want to stick your nose into what’s none of your business?’

‘If Grandpa’s left me land then it is my business.’

‘Nonsense. And don’t call him Grandpa. You’re out of your depth.’

So I was. But I was going.

‘Then I’m coming with you,’ she’d snapped and I almost dropped the phone. Me and Muriel together on an island on the other side of the world? The thought was unbelievable. But it seemed it was happening.

We flew to Sydney, where Richard had organised a seaplane flight for the last leg. That was where the first hitch occurred. Muriel’s baggage—all of it—was happily still with us, but mine seemed to have detoured to places unknown.

At least Drifter hadn’t been misplaced. I checked on her as we transferred and her look of black depression hadn’t changed. ‘I’m taking you home, girl,’ I told her again, but she looked less than impressed.

There wasn’t a lot I could do to make things better. On we went, with me thanking my stars that at least I had a toothbrush and phone charger in my carry-on. Muriel griped about the size of the seaplane, the bumpiness of the flight and the fact that they didn’t serve champagne. I watched the sapphire sea and the amazing islands we were flying over. I checked out the gorgeous fake tan on my arms and imagined how it would feel when there was a real sun-glow on them. Jen Kelly. Beach Bunny. Islander.

And what an island! It came into view, sunlit and stunning, mountainous inland, with undulating farmland near the coast and the sea stretching on forever. As we descended, details came into focus. The plane circled low before landing and I had an eagle’s view of the town. There was a miniscule harbour with fishing boats tied up at a quaint little wharf, and a few whitewashed shops running up the hill. General store. Post office. Church and school. A long brick building with cyclone fencing all around. Could that be Henry’s boarding house? I could see little else.

Uh-oh, I thought. What would Muriel do without shopping?

But the island was beautiful. There were masses of frangipani trees and jacarandas behind secluded coves with sandy beaches. Then there were the mountains, soaring skyward like great green sentinels. From sea level they seemed to be covered in rainforest, undisturbed forever.

The seaplane swept down onto the water, pulling up smartly at a floating platform attached to the town’s only jetty. Two people were on the wharf, a man and a woman, both elderly, waving us a welcome.

It took us time to get out of the plane. Muriel objected to the wobble of the floating platform. In the end the pilot picked her up and carried her to the wharf, with querulous objections all the way. Drifter slunk out of her cage, cringing against my legs.

‘Nearly home,’ I told her. I knelt down and gave her a hug. The hug comforted me, even if she didn’t seem to notice.

The pilot of the seaplane had radioed ahead for a hire car to meet us. Here was our second glitch. The guy on the wharf ran the hire-car business, he told me. Or … not so much a business as an occasional hobby. Very occasional.

‘Well, you see, there’s one hire car on the entire island. And it’s not so much a car as a beach buggy.’

No roof.

‘But it’s not raining.’ The guy looked old enough to have retired twenty years ago. His eyes were firmly facing away from storm clouds gathering ominously in the distance.

‘Where do you folks say you’re from?’ asked his smiley, white-haired wife.

‘Manhattan.’ I wasn’t concentrating on niceties. Our beach buggy looked tied up with string.

‘Well. That’s some journey. And with a dog? Most visitors don’t bring dogs.’ And then she paused. ‘Hey, that’s not Henry’s dog, is it?’

‘Mind your own business,’ Muriel snapped. ‘Let’s go.’

But she wasn’t suggesting we reboard the plane. Her face was set for the distant hills. For a farm she’d once known?

My cell phone pinged as reception returned and I turned away for a moment to read. I had two messages. One was from Richard.

Hope flight safe. Advise you’ve arrived. Check every property sold for last twelve months with price per acre. List all advantages of yours over theirs/vice versa. Send info here and I’ll have it checked. Don’t sell without checking in.

I hadn’t even seen the place. No, I wouldn’t sell yet, with or without his say-so.

The second was from Isabella.

Have you seen it? Are instructors cute? I so want to come see. Pregnancy’s the pits. Send pics.

No pictures yet, and I hadn’t thought of instructors. Does a surfing school come with instructors?

But Muriel was sighing with true drama queen impatience so I tossed the phone into the console and got on with the last part of the journey.

‘Sorry.’ I gave the hire-car couple my best apologetic smile as they helped me load the buggy, setting Drifter in the back and the glowering Muriel in the passenger seat. She grumped and refused to say thank you. ‘My grandmother has jet lag.’

Which was partly true. Jet lag and a strong inclination to be unpleasant.

But I had to ask directions.

‘I know how to get there,’ Muriel told me, as if I was an idiot for not knowing. ‘Drive now, Jennifer.’

We made a fast stop at the general store, which looked like something out of a retro movie. The lady in there was full of questions but Muriel sat in the buggy and hissed impatience. I bought essentials: milk, bread, eggs, tea. I also bought coffee, though I was deeply dubious when I saw the No Name packaging. Then I drove for twenty minutes on the wrong side of windy, unmade roads. Thinking about surfing instructors. And beach. And that this island really was spectacular. And also that, struggling with jet lag and a surfeit of Muriel, I could use a very long sleep.

Finally we turned onto a rough farm track on the east coast. By now the clouds had blocked the sun, and they were getting blacker. I was praying we beat the rain, but despite Muriel’s grumpiness, even despite the prospect of the coffee I’d just bought, I was still feeling in control. My tan was still fantastic. I was about to take ownership of my domain.

But when our jolty little beach buggy made the last coastal curve before the farm, the illusion of control shattered.

What I saw was an ancient, weathered cottage, an aged brick building to the side—a dairy?—a weird array of surfboards propped up against a ramshackle shed and a motley collection of other, smaller sheds. An overgrown jungle of a garden surrounded the house, and a few lanky cows lined up at the fence. The only thing even vaguely like what I’d imagined was the surf in the distance.

This was not a surf school. This was a maritime artefact—with cows.

‘Is this it?’ I asked Muriel. I pulled up by the surfboard shed and stared out in dismay.

‘Do you mind? If I’d known you planned to drive like a lunatic, I’d never have come.’

‘You know neither of us had a choice. Muriel, what is this place?’

‘What does it look like? House, barn, cows. Farm. I told you.’

‘These sheds aren’t barns.’

‘Then they’re haysheds. Or dairies. I forget.’

‘So what’s with the surfboards? They look ancient. This doesn’t look like a surf school.’

‘It was a farm when I was here. And a surf school? I knew that was nonsense.’

‘Then what’s with the sign?’

The shed, supported by the mismatched family of surfboards, was decorated with a sign that covered most of the rusty iron roof. The sign was astonishing, but Muriel’s glance was disdainful. This farm must have been part of her life fifty years ago, but she’d moved on.

At least now I could understand why Muriel’s secret marriage had been so brief. The only thing I didn’t understand was how a perfect, airbrushed Manhattan doll like Muriel had ever been persuaded to come here in the first place.

Despite the neglect, it seemed like this farm might once have been idyllic, but right now I was concentrating on the derelict buildings. And the sign. Red paint on rusted iron.

DR J.R. KELLY’S SURFING SCHOOL.

‘Grandpa was called Henry, right?’ I said slowly, feeling stunned.

‘Yes.’ A terse snap.

‘So Dr J.R. Kelly … That would stand for Dr Jennifer Rainbow Kelly?’ The Rainbow’s from my mother. It was once my only name but my grandmother added Jennifer when I was seven and I’ve been known by nothing else since. ‘How did Grandpa know my name?’

Silence.

‘Grandma …’

‘Don’t call me that. How would I know anything about your grandfather?’

‘You were married to him.’

‘Momentarily. Fifty years ago.’

‘Did he know he had a granddaughter?’

‘I didn’t tell him anything. I haven’t been in contact with him since your mother …’ She caught herself, shaking her head as if ridding herself of bad memories. ‘No. Your existence was none of his business.’

‘Since my mother what?’ I was still clutching the steering wheel as if it gave me some measure of control. It clearly didn’t.

‘You don’t need to know.’

‘Are you intending to tell me anything?’

‘I came with you, didn’t I? I gave you directions. It’s enough. Leave me alone.’ Muriel’s face had the determined look of a bulldog with a secret bone.

‘Fine.’ I believe I was snarling. ‘If you want to be mean about it, good. We’ll stay here then, shall we? We’ll make ourselves comfortable in a rundown farm owned by my dead grandfather. A farm that’s been left to me by a man I didn’t know existed, but who knew enough about me to be painting my name on signs. A man I can’t know about, because you say so.’

‘It’s nothing to do with you.’

‘It is. Which is why we’re here. If you’re not going to be helpful then go home.’

But Muriel’s face was set. ‘I’m staying. Just leave me alone. Do what you like. Learn to surf. Teach yourself to milk cows.’

‘Oh, right. As if that’s going to happen.’

‘If I can, anyone can.’

I think my jaw must have dropped around my ankles. My grandmother was a delicate, fragile society dame. ‘You can surf? You can milk a cow?’

‘What else do you think I’d milk? Pigs? I’d imagine my surfboard’s still over there. A Malibu.’

‘A Malibu … surfboard?’

‘Of course a Malibu surfboard. See? You know nothing. Mine’s one of the first smaller boards—the ones that really sliced. One of the originals.’ Unbelievably, there was a note of pride in her voice.

‘The ones that really sliced,’ I repeated dumbly. ‘One of the original … what?’

‘Cutback Malibus,’ Muriel said, as if I was stupid. Which was how I was feeling.

‘Darrylin Zanuck had the first of the quick boards,’ she added, and she no longer seemed to be talking to me. She was staring at the line of propped-up boards. ‘Darrylin was Tommy Zahn’s girlfriend, and Joe Quigg designed the board just for her. It was such a breakthrough. Light and easy and short enough to fit in the back of her convertible, it was just right for a girl. Before she knew it, the guys all wanted the same. Darrylin had a fight on her hands to keep it. You can turn four times faster than on the older boards, banking and turning on a dime. My board’s just like hers—a varnished, redwood and balsa ten-footer, sealed with fibreglass and resin. It has fifty-fifty rails, a curved rail rocker, a flat, planning bottom and a fin. Darrylin’s board was the loosest board on the surf scene and mine was as good or better.’

She may just as well have suddenly started talking Swahili. ‘Who’s Tommy Zahn?’ I asked weakly.

But Muriel had withdrawn again into the distant place she’d been all her life. Still huddled in the passenger seat she motioned towards the house. ‘Drive.’

‘But—’

‘Jennifer! Drive. It’s starting to rain.’ She sat there, passive in her designer frock, with her Manolo Blahnik shoes and her pearls that were worth a king’s ransom, silent once more.

Muriel had surfed? Muriel had milked cows?

But she was right. It was starting to rain, and I had a surfing school to discover. The dog was quivering in the back seat. The surfboard shed looked big enough to take the buggy so I drove in there.

It seemed we were home—sort of.

image

Five hours later, mid-storm, I was staring out into the night and accepting that coming here was a really big mistake.

There hadn’t seemed much choice, though. There was nowhere to stay in town but one boarded-up hostel, and even if it was habitable Muriel had no intention of staying there. It was Henry’s house or nothing.

Once we’d figured out which of the rusty keys under the doormat opened the house, it had taken ages to get the main bedroom to a standard she found acceptable. It had obviously been Henry’s room, gorgeous, with fantastic sea views, but it looked as if it’d been empty since Henry’s death. Muriel seemed to be using irritation to disguise emotion. She’d stood back and thrown directions while I worked. While lightning played outside, while the rain pelted down, filling the house with the smell of salt, sea and heavy rain, I’d dusted and swept and shaken out bedding. Then I’d made up Muriel’s bed with her personal linen until finally Her Ladyship was satisfied.

I’d made up a scratch meal—eggs and toast—but she’d eaten nothing. She’d retired to bed, closing the door behind her.

I couldn’t let it bother me. There was more work to do if I wanted to sleep tonight.

The only other bedroom seemed to be furnished for a young girl, with faded pink curtains, a narrow bed with a pink eiderdown, a pink bureau and a couple of pink stuffed toys on the dresser. Eerily, though, none of the faded pink collection looked in the slightest bit used.

I don’t think anyone had been in this room for decades. The windows were loose in their frames and sand had oozed in, filling every available niche. I had to shovel the sand out the window— thankfully it was in the lee of the storm. Even if my luggage had arrived, I hadn’t packed personal sheets and the bed was made up with linen that almost crackled with age. It smelled and felt like something out of Dickens, only instead of the bridal splendour of Miss Havisham’s sitting room, this was a little girl’s room.

And all the time the dog watched me. She’d jumped out of the buggy when we’d arrived and nosed her way into the house in a way that suggested she knew it well, but there was no joy about her. She’d eaten an egg as if she was doing me a favour. She still carried that air of desolate resignation.

It was starting to get to me. The whole situation was getting to me.

What had I expected? That Muriel would respond with joy? That kindly neighbours would be ready and waiting to take her under their wing? That bronzed surf instructors would be racing up the beach whooping a welcome?

There were none of the above, and the dog and I were feeling its lack.

Then, adding to my growing sense of disquiet in this creaky, windy house, I tugged open the first drawer of the pink painted bureau and found letters. Lots of letters. The paper was flaking with age. The envelopes were filed in what seemed to be date order, all addressed but seemingly never closed, stamped or sent. It was as if they were waiting to have something added to them before sending.

And they were addressed to me. All of them. Jennifer Rainbow Kelly. Once more, the use of a name that was almost forgotten.

I lifted the first one—dated when I was seven—and started reading.

Jennifer,

I understand you’ve reached your grandmother’s, and that you’re now Jennifer. Rainbow was always a fanciful name anyway—you can’t build a sensible life called Rainbow and I believe you need to be sensible. Meanwhile, I hope you’ve forgotten our fleeting meeting. If you haven’t, then do it now. I didn’t want to force my existence on you, just as I shouldn’t be writing.

You needed me, but I hope you don’t need me again.

It’s probably for the best if I don’t post this. Just forget, as your grandmother has. But I trust you’re safe and well.

Your grandfather, Henry.

I stared at the stacks and stacks of letters and felt prickles down my spine. Ghosts? I read a couple more.

After the first they became the sort of formal letters any grandpa might send to his grandkid. Normal stuff. I hope you’re liking school. Happy birthday. Here’s ten dollars to buy yourself a Christmas gift.

There was actual money enclosed.

Feeling more and more spooked, I replaced the ones I’d read and crossed the room to draw doodlebugs on the sand-coated window.

I needed to let Richard know I’d arrived safely. I needed to respond—professionally—to Isabella.

But I had a problem. I’d left my phone in the buggy. It was parked in one of the outside shacks and retrieving it now seemed just plain scary.

I stared out the window through the tangle of tropical undergrowth. The storm had passed while I read the letters. The moon had emerged to cast a glimmer of light on the garden. The surfboards loomed in the background like tall, threatening ghosts.

Ghosts?

Get a grip.

‘You want to come outside with me?’ I asked Drifter, but she heaved a great sigh, dropped her head between her front paws and did a floor rug imitation. She was going nowhere.

If Richard was in my place he’d have called me by now, I told myself. But then, Richard’s planes were never delayed. Richard’s baggage was never lost. What’s more, Richard would never have left his phone in the stupid beach buggy, forcing him outside in the dark in this weird place, risking death by vipers, strangler vines, falling surfboards, killer whatever-animals-hunted-in-this-place …

Sheesh, Jennifer.

‘I should wake Muriel and make her come with me,’ I said out loud. Oh, great. Wasn’t talking to yourself the first sign of madness? Stranded and loopy. Terrific.

But I couldn’t wake Muriel. In truth, she had me worried. Once we’d parked the buggy, despite the rain, she’d walked over to the row of surfboards and fingered one of the smaller ones. She hadn’t said a word. Her face, though, had sort of shrivelled, and when she’d walked inside it had grown worse.

‘It’s exactly as I left it,’ she’d said, but she was speaking to herself. Crossing to the mantel, she’d lifted a dusty framed photograph of a handsome young air force officer and his bride. It was Muriel’s wedding, all those years ago.

Was the uniform from the Vietnam War? Nothing else fit. Had Henry been in the US all those years ago? At least that would explain how he and Muriel had met.

I’d watched in silence as Muriel stared at the faded picture. Finally her eyes had filled with tears.

‘He hasn’t changed a thing,’ she’d said but she was speaking to herself. ‘He’s even polished my board. For all these years …’

The knowledge seemed to have knocked the stuffing out of her.

She’d roused to order the cleaning but then she’d shrunk into the too-big bed with the faded furnishings that must once have been luxurious. She’d lain against the pillows in her exquisitely embroidered silk negligee, and she’d looked … pathetic.

‘Not for me. Not for me, Henry,’ she’d said and it was as if she was talking to a ghost.

I thought about the photo, the waxed, ancient surfboard and the letters. If it was getting to me, how much worse was it for Muriel?

So Muriel was in no state to be woken, and right now I needed to focus on Richard. He’d be expecting me to call. I needed to do it. Care and Maintenance of Fiancés 101.

But it’s dark outside, the jelly side of me quavered.

Just do it. What could be out there? And who could possibly see you?

That was another reason why I was reluctant to go outside. Muriel’s gear—all of it—had arrived along with us, but I had nothing. My initial idea of borrowing something had been treated with the contempt it clearly deserved. I’m not much taller than Grandma but I’m a size ten compared to her size six. Cuddly. Which Grandma has never, ever been. Nothing of hers could fit me.

I couldn’t stay in my travelling clothes forever, but in the bottom of the bedroom dresser, I’d found six pairs of men’s pyjamas, still in their plastic wrapping. I also found twenty pairs of socks and a bundle of jocks, all unopened. Come the revolution, Grandpa had obviously intended to remain sartorially splendid. So now I was wearing red pyjamas with purple stripes, four or five sizes too big, plus a pair of ancient flip-flops I’d found in a box at the back door. Large flip-flops.

I tried to reassure myself that my appearance didn’t matter. There was no one for miles except Grandma, one depressed dog and some cows.

So grab a torch and go.

Outside the wind had eased to nothing, and the night-time view was so amazing it took my breath away. The moon was intermittently exposed as wispy clouds scudded past, and beyond were stars as I’d never seen them before. I’d never realised the sky was so close.

I should have savoured it, but it was all a bit scary. Foreign. Lonely. I walked through the long, soaking grass of the garden, taking giant steps, hoping that I wouldn’t hit a viper, or whatever poisonous creature lived here. Then, just as I reached the shed, I paused.

I could see the beach only fifty yards away, down the path by the shed. The moon had come out from behind the clouds. The wet sand sort of shimmered in the moonlight.

There was something down there. A mound, vaguely moving.

Was I imagining it? It was a dark, rounded shape, like a rock. It was past the high tide mark, almost at the neck of the path, and it was definitely moving.

A turtle?

Yes! I shone my flashlight down and there she was, a great, lumbering creature, her flippers splayed out around her. She looked …

Like she was laying eggs! She turned towards the source of the light, as if annoyed at my intrusion. Awed beyond belief, I flicked the flashlight off and walked slowly forward along the sandy track until I was about ten feet away from her. Stooping, I watched her.

Once the flashlight was off she ignored me. She was in the throes of birthing, and as long as I wasn’t getting in the way, she had better things to do than say hello.

My jet lag forgotten, I knelt on the damp sand and watched.

Each egg, the size of a normal hen’s but softer, squished a bit as it fell on top of its predecessors. Each was brilliant white and perfectly round.

I wanted to go wake Muriel. I wanted to ring Richard and say get here now. I did neither. I felt small and overwhelmed, but … honoured. It was almost the same feeling as standing back after a delivery, watching a mother with a newborn.

A miracle.

It’s why I do what I do.

I watched on, staying as still as I could, until she seemed to run out of eggs. Then she stared up at me as if I was interfering with what she wanted to do next. Clearly she wanted me gone. Which was fine by me. My butt was wet and I was bordering on shivering. I bade her a congratulatory goodnight, and made my way back up to the house, still feeling awed. When I reached the top of the path and looked back, she’d started scraping sand on top of the eggs.

Baby turtles on my beach. My beach. My sand. How cool was that?

I even thought about composing a text to Isabella: There’s a turtle laying eggs on MY beach!

Grinning, I turned and walked into the shed where I’d parked the buggy. There was grass right into the shed and my feet were soggy. I shivered—and then I stopped.

A vehicle was coming along the track towards the house. Fast.

I was in the dark in Grandpa’s wet pyjamas. Someone was coming. This was suddenly scary again.

It was too late to bolt for the house. I squashed close against the ancient woodwork and tried to look invisible. Tried to stop my heart hammering.

The car stopped not ten yards from me. Hinges squeaked. I heard a door slam, followed by the sound of someone running past my shed towards the beach.

I didn’t want to be here.

I gave it a minute and then peered cautiously around the shed door. It was a van, with its back doors open, and it looked abandoned in the moonlight.

Let’s go, I told myself, even though my feet didn’t want to move. But somehow I made them. I ran towards the house, but as I ran, I glanced back at the beach.

My turtle had turned back to the sea, but the intruder, a big, powerful-looking guy, had reached her. He stooped over and lifted her, grunting with the effort.

The turtle was seriously big but he hauled her back up the beach towards the path, staggering a bit but heading for the van.

He heaved the turtle into the back of the van and slammed the doors shut.

And something inside me snapped.

‘Put her back!’ I yelled before I even realised I’d intended opening my mouth.

He swung around like he’d been shot.

He looked … like a pirate.

As a first impression it was ridiculous, but I was past making sense. It was night and it was dark and it was frightening. He was wearing some sort of bandana. There was no eye patch and there was no wooden leg—though come to think of it I hadn’t checked his legs—and there wasn’t even a parrot on his shoulder, but I wasn’t concentrating on details.

‘Put the turtle back!’ I yelled again, and launched myself forward between him and his van, superwoman personified. Which was maybe not the best move in the dark when I wasn’t actually superwoman. I stubbed my foot on a rock and lurched sideways, heading for the ground.

He moved fast. He caught me by the shoulders and held me, stopping my fall. I hauled back. He didn’t let me go, but I was high on adrenaline.

‘Don’t you dare hurt my turtle!’

In the moonlight I could see the low-life was smiling. It was a crooked, devil-may-care, bad-boy smile, but it was enough to give me pause. I stared at the man’s eyes like I was caught in headlights.

I wrenched back and he let me go. Then I should have run, but the urgent need to clutch my pyjama bottoms stopped me. This didn’t make for a good start. I still had my flashlight in my hand. I flicked the switch and nearly blinded him.

He was lean-jawed and unshaven. He had matted brown hair that looked like it hadn’t seen a brush for months, and his eyes were incredibly blue.

This was good, I told myself, my brain operating at a level somewhere between stunned and hysterical. At least I could give a description of my turtle-smuggler-and-maybe-axe-murderer. He looked like a pirate, officer. Ragged clothes, muscled chest, tall and rangy with dangerous eyes …

‘Um … hi,’ he said. ‘Nice to meet you, too, fair lady.’

The guy seemed to be expecting some sort of response.

Come on, Jennifer, you can do this.

‘Put the turtle back,’ I said again, feeling as weak and stupid as I must have sounded.

‘No,’ he said. Then he looked at me—really looked at me— obviously seeing the fading adrenaline and the fear. His blue eyes softened. ‘Hey, there’s no reason to get your knickers in a twist. I’m not interested in turtle soup. I’m organising a spot of carapace surgery.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘Shell repair,’ he explained, like he was talking to a three-year-old. He tilted his head to one side, smiling, watching me with interest. ‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to scare you. I’ve been watching for her for the last few nights, checking whenever I could. I’ve been out on a call tonight and nearly missed her. I’m very glad I didn’t.’

His voice was deep and rich and accented. Scottish? A little. Mostly Australian.

‘Who are you?’ I managed.

His smile faded. Maybe he was a bit shocked himself. Maybe the sight of a Manhattan obstetrician in her grandpa’s pyjamas was a bit out of left field.

‘I’m John McLachlan. Jack.’ He placed his hands on my shoulders again. I flinched, but his hands stayed put. ‘I told you, there’s no need to look terrified.’

‘I’m not terrified,’ I lied, and pointed the flashlight into his eyes again.

He was maybe in his mid-thirties. His deep brown hair was bleached to almost gold at the ends, tangling and curling to his collar. He was wearing heavy, scuffed boots, jeans with frayed knees, and an unbuttoned flannel shirt.

He put his hand on the flashlight and manoeuvred the beam from his face.

‘What do you mean, shell repair? And what are you doing here anyway? This is private property.’

‘I work here.’

‘You work here?’

‘I work in the garden,’ he said. And then he paused. From the house came a streak of white fur. It was Drifter, head down, a torpedo heading straight for him. She got within six feet and launched herself into the air. Somehow he held out his arms and caught her— not bad for a big dog—and the next minute they were bonded. The dog was a bundle of canine ecstasy, and Jack had a great, goofy smile which totally transformed his face.

‘Drifter.’ He was burying his face in her thick coat. ‘You’re home, girl. Eh, lass, I’ve missed you.’

The feeling was obviously mutual. I was left with nothing to do except wait until bonding rituals had been completed. Which took a while.

But finally they were done. Drifter was set down. She wriggled at his feet, prostrating herself before him, quivering with delight.

‘You brought her home,’ he said at last, with deep satisfaction. ‘I can’t tell you how grateful I am to see her again.’

‘Was it you who sent her to me?’

‘Yes, but reluctantly.’ He shoved a hand out and took mine, whether or not scared-and-insular-me was comfortable with his rough, broad hand. ‘Let’s do the introductions again. As I said, I’m Jack McLachlan. I’m your closest neighbour.’ He hesitated. ‘That is, if you’re Dr Kelly?’ He glanced at my hair, which with this humidity had reverted to its natural untamed riot. ‘With that hair I guess you can’t be anyone else.’

‘I’m Jennifer Kelly. But how did you know?’

‘Your grandpa told me you had the same hair as his. His hair was like yours, almost to the end.’

My grandpa had known more about me than my name?

‘You sent me the dog?’

‘Henry’s will was unequivocal.’ He stooped and faced Drifter nose to nose. ‘I hated letting you go, girl, but Henry seemed to think she’d be more likely to come if he sent you as an envoy.’

What the … ‘So you just sent her,’ I stammered. ‘Without warning. She just arrived. Anything could have happened to her.’

He straightened and faced me, impassive. ‘There was nothing I could do about it,’ he said laconically. ‘The lawyers from Sydney arrived and took her away. They asked if I’d keep an eye on the place until you came, but Drifter was Henry’s dog. He’d even trained her to protect the nesting sites. It seemed cruel to send her away, but her fate was his decision.’

There was so much about this I didn’t understand.

The turtle was in the van. That’s where I’d go, I decided. The turtle seemed the easiest thing to focus on. ‘So … what are you doing with the turtle?’

‘She has a cracked shell. She has a tracking number—you can see it on the edge of her shell—and apparently she’s been coming here for years. Bridget calls her Tootsie. I live up on the headland—Henry’s place and ours have the only access to Turtle Bay and I check most nights. If you look along the beach tomorrow you’ll see markers. I try to mark every nest so we can get onto it fast if anything’s disturbed. I was on the beach three nights ago when she laid the last lot of eggs and saw the crack in her shell, but I can’t carry turtles up our steps. I thought she’d take longer but by the time I fetched the van she’d gone. They often come ashore more than once to lay all their eggs so I’ve been hoping she’d come again. I almost missed her this time, too.’

I thought about this, filtering what seemed important. ‘You can fix her shell?’

‘I have a mate who can. There might be a problem at the base of the crack. It could be infected, but if it is, Ewan’ll fix it. He’s a vet but he makes the occasional surfboard so he’s not bad at fibreglassing. Hopefully she’ll keep coming back to lay her eggs so we can check it year to year. He’ll have her fixed and away in no time.’

‘Really?’

‘Really. She’s a green turtle, endangered. She’s pretty special.’

‘But …’ What else to focus on? ‘You drove down my driveway. You’re on my property.’ It sounded feeble, even to me, but I’d been scared. Feeble was pretty much how I was feeling. Luckily he didn’t seem offended.

‘Needs must,’ he said cheerfully. ‘But I’m out of here now. Things to do, places to go.’ He turned towards the van.

But he didn’t get far. Drifter launched herself at him like she was drowning, desperation in every inch of her body.

‘Hey, girl,’ he said, softening, crouching again. ‘You have a new mistress now.’

‘She’s not mine.’

‘She was your grandpa’s. She goes with the farm.’

‘I don’t want … I can’t …’

There was a long pause. Finally he shrugged. ‘You’ll need to sort it with the lawyers but if you don’t want her, I’m happy to keep her. That’s probably what your grandpa expected anyway—that you’d come and get rid of everything. Which is fine by me. I told the lawyers I’d keep taking care of the place until you came. Henry’s veggie patch is second to none, but I hardly have time to keep it in order.’

I’d walked through the vegetable garden. It was the only well-tended area in the place. In this subtropical climate it must be a huge task to keep it productive.

‘That’s … good of you.’ Without thinking, I swung the flashlight towards him again. He took my wrist and gently removed the flashlight from my grasp.

I looked up. Which was maybe a mistake.

Jack McLachlan was about six-two, which meant he towered over me. I was wearing Grandpa’s flip-flops and too-big pyjamas. My stupid hair was coiling crazily around my face. When it was wet it did a Shirley Temple spiral which might have been cute when I was seven.

I felt totally intimidated. I felt very, very small.

‘I’m sorry I yelled at you,’ I managed. ‘If you want to keep taking vegetables or rescuing turtles, you’re very welcome. But I need to go inside. I’m … I’m in my pyjamas.’

‘You’re in Henry’s pyjamas.’ His left eyebrow hiked—was he teasing? ‘You found his stash?’

‘Yes, I …’

‘He liked buying in bulk, did Henry. He bought online through Carrie, and he liked a good deal. He’ll be glad they’re not wasted. If you don’t mind me saying, they look a whole lot better on you than they ever did on Henry.’

I flushed—how stupid was that?—but he didn’t appear to notice. He stood aside to let me move away.

But for some reason I didn’t. ‘I’m cold,’ I said.

He nodded again, his face thoughtful as he checked out my feet. ‘You’ll be needing something more substantial if you’re night wandering. Not that I’m criticising your footwear. It’s very fetching.’

My flush was turning into a full-on blush. Luckily he was looking at my flip-flops.

‘My bag’s somewhere between here and New York.’

It wasn’t just a bag; it was my brand new Gucci suitcase, but I looked at Jack’s disgusting boots and I knew he wasn’t going to sympathise. Sure enough, he didn’t.

‘You arrived from the US today?’

‘Yes. We hired a car in town.’

‘Harold’s beach buggy?’ He beamed. ‘You’re a brave woman. Don’t flick the wiper switch, whatever you do. Harold wedges wipers in to make it look like there’s still a windshield. The last hirer almost lost an eye.’

Despite his smile I had the feeling he was assessing me. ‘I didn’t mean to disturb you,’ he said, and his tone was suddenly apologetic. ‘Clive told me you and your grandma were arriving soon, and if I hadn’t seen Tootsie come to shore I’d have kept my distance. But speaking of Tootsie, I’d better get her to turtle hospital.’

‘Okay. But give me my torch back. I need to fetch my phone from the buggy. From the shed.’

‘Your buggy’s in the woodshed?’

I stared across at the rickety shed supporting the surfboards. The boards looked as if they’d been there forever. Ferns were growing up around them as if they belonged, with vines tying it all together. The only new part of the whole thing was the paint on the sign. The buggy was inside.

‘It was raining when we arrived,’ I said. ‘I didn’t want the buggy to fill with water. The shed was empty and I thought it was a garage.’

‘Henry didn’t need a garage. Your grandpa walked and surfed. He didn’t do much else.’

‘Did he really run a surf school?’

Jack hesitated. ‘He thought about running a surf school,’ he said at last. ‘Sometimes.’ His voice was suddenly cold.

Why the change?

This man had known my grandfather. The knowledge was unsettling. Until now Henry Kelly had seemed a vague shadow from Grandma’s past. He’d been a man I’d never met and who had nothing to do with me.

But this man had known Henry well enough to recognise his pyjamas. To know about his routine and his hopes for the future.

It was weird, but as I stood by the vegetable garden Henry had tended, speaking about him with a man who’d known him, it was like a gentle ghost had drifted from nowhere.

I stared down at the dog. Drifter. Grandpa’s dog.

I’d just given her away, and all of a sudden it felt wrong.

What was I thinking? I was too tired for all this.

‘Whatever you call the dump holding the surfboards, that’s where my buggy is,’ I said, trying to sound efficient. ‘And my phone, too. I’ll fetch it and then I need to go to bed.’

‘Woodsheds are havens for nasties.’

Nasties. That was a word to make a girl pause. ‘What sort of nasties?’

‘Joe Blakes.’

‘Joe Blakes?’

‘Sorry. Snakes. That’s Aussie speak.’

‘You sound Scottish.’

‘A lot of us islanders have Scottish heritage. It’s a tough call to breed it out of us, but returning to snakes…’

‘Let’s not.’

He grinned. ‘Lady, you need to think about them. As long as you’re noisy they’ll normally scadoodle. I have a repertoire for woodchopping and by the time I launch into “Auld Lang Syne” the snakes are scadoodling for their lives. But tonight’s rain has cooled things off, which means our snakes will be slow and the woodshed’s a favourite place for them to shelter. Not even “Scotland the Brave” on a bagpipe will move them tonight.’ His brows wriggled expressively, and I knew he was laughing at me. ‘Until you stand on one, of course. Then they’ll move. Goodness me, will they move.’

‘Then I don’t need my phone,’ I said, distilling what was important and coming to the only conclusion possible.

‘I’ll get it for you.’

‘Don’t snakes bite you?’

‘I’m tough.’ There was that grin again—mesmerising. ‘More to the point, I’m wearing boots so thick they’d break their fangs. As opposed to you. That footwear might be all the go in the States…’

‘I told you—they’re Henry’s flip-flops.’

‘We call them thongs over here,’ he said, his grin widening. ‘There’s a recipe for international misunderstanding. If I were to tell a chap from, say, California that our women wear thongs to do their grocery shopping, he’d get all the wrong ideas.’

‘I guess he would.’ The night was spinning away from me once again. I took a deep breath and tried really hard to sound sensible. ‘My phone’s in the box thing between the seats. Would you mind grabbing it?’

‘Sure. Drifter, stay and guard the lady. One phone coming up.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Think nothing of it. Your grandpa would expect me to be nice to you and I abide by his wishes.’

image

That was the end of my first neighbourly visit and it left me badly shaken.

As soon as Jack handed me my phone and reversed the van containing Drifter and the turtle, I bolted into the house. I headed for my pink and sandy bedroom, checked reception—good, thank heaven—and phoned home almost without pausing for breath.

‘The place is awful,’ I told Richard.

There was a pause while he thought things through. He never moved in a rush, my Richard. It was one of the things I loved about him. Living with Muriel had been chaotic. Richard was an oasis of calm in comparison. Unflurried. Considered.

‘What do you mean?’ he asked. ‘Is the farm worthless? Have you wasted a trip?’

‘I don’t know. It’s sort of…’ There was a sudden loud croak from under the window and then a responding bellow that must have come from a cow. I was still shaking and the noises didn’t help. ‘I saw a turtle and it was cool but the whole place is really … rustic.’

‘It is a farm.’

‘Yes, but it’s sandy.’

‘So it’s a farm by the sea.’ He was laughing at me. Okay, I was being dumb.

‘I’ve lost my baggage.’

‘The airline rang here and apologised,’ he said, patient as well as amused. ‘It’s in Sydney now. Luckily there’s another seaplane out to the island tomorrow morning. You should get it then.’

Richard steadied me. He always did. He was my fiancé who loved me.

‘There’s no need for you to stay if the place is a knock-down proposition,’ he said, moving on. ‘Check the property prices tomorrow. That’s really all you need to do. Once you’re sure of values we can put the place on the market from here.’

‘It’s not completely derelict,’ I admitted. ‘And maybe I do need to find out about Grandpa. Richard, Henry’s been writing me letters he’s never posted. They’re all here. And this place … Old surfboards. Signs. It’s weird.’

‘I can believe that,’ Richard said dryly. ‘If he was anything like Muriel then weird’s almost a given.’

I sighed. Richard’s opinion of Muriel has never been flattering. Okay, neither has mine, but it’s always felt wrong for Richard to criticise her. Richard has a prestigious and supportive family. I have Muriel. She’s not ideal family, but she’s all I have.

‘Maybe I need to stay because of Muriel,’ I told him, thinking it through as I talked. ‘Maybe she needs to lay some ghosts.’

‘She can lay all the ghosts she wants from here. Put it on the market and come home.’

I stared down at my feet, wiggling my toes in my … thongs. I’d swept the sand from the room but not thoroughly enough. My toes were wet and there was sand sticking to them.

‘I’ve come too far not to see this through,’ I said. ‘I’ll stay a few days and see if I can’t get any information out of Muriel about Henry. But I’ll be back as soon as I can.’

‘Just cross your fingers that the Clayburgh baby doesn’t come early. It’s a risk.’

‘It’s not much of a risk. We discussed it.’

But Richard had moved on. ‘I need to go.’ I could imagine him glancing at his watch as he turned from his window framing the Manhattan skyline. ‘I’m operating in forty minutes before heading back to the conference. If there’s nothing else…’

‘There’s nothing else.’

‘Goodbye then, sweetheart,’ he said and the phone went dead before I could reply.

I should be relieved. I’d done what I’d needed to do. Now I could sleep.

I wiped my feet, then settled into my little-girl bed and tried to conjure up Richard’s face. My fiancé. My future.

It didn’t work. I did drift off eventually, but it wasn’t Richard I was thinking about. It was turtles and Joe Blakes and a grandpa who wrote me letters.

And pirates?

Find out more about Home to Turtle Bay, available December 2018

Brothers of the Vine

Brothers of the Vine Forever Evermore

Forever Evermore Women of W.A.R.

Women of W.A.R.